- Horacio Rodriguez

Borders are a complicated concept—often arbitrary, and generally used to define who should belong on one side or another. For Horacio Rodriguez, his journey as an artist has been one of exploring every part of that concept, often on a very personal level.

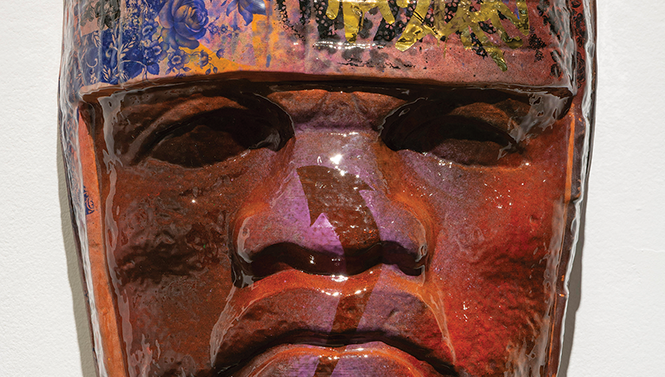

The 15th installment of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts' salt series showcases former University of Utah teaching fellow and Alta High School art teacher Rodriguez, focusing on his explorations of his Mexican and Puerto Rican history through works that are in conversation with the ancient art of Mesoamerica. Rodriguez's own sculptures—including digital photography superimposed on large-scale figures—sit alongside some of the actual pre-Columbian artifacts that inspired them.

Rodriguez traces his artist "origin story" back to his childhood growing up in Houston, Texas. His mother worked in the city's museum district, and he describes how in the summers, "I'd just spend my time walking around in museums. I took art classes, and I definitely knew by high school [that I wanted to be an artist]."

Yet he also identifies another part of his childhood that would have a huge impact on his art and his identity in a broader sense: growing up as a Latino-American, yet feeling disconnected from the heritage of his Mexican father and Puerto Rican mother. "I grew up in a very upper-middle-class neighborhood," Rodriguez says. "You'd get in trouble if you spoke Spanish in school. I learned quickly to assimilate, at the cost of my heritage and my language. ... We'd visit family in Puerto Rico, and they'd make fun of me because I spoke Spanish like someone who was white and had learned Spanish."

"I now realize there's a lot of people in my situation: We don't feel like we fit in completely with the dominant culture we grew up in, but also don't feel comfortable with the cultures [our] parents are from. A lot of my art in the beginning was dealing with that."

Later, after graduating from Montana State University, he began traveling in Latin America, particularly though his father's home country of Mexico. He started collecting pre-Columbian art, and eventually began using 3D printing and modeling processes to generate replicas of those pieces that he could manipulate. "I came up with this idea of what I call an 'uninvited collaboration' [between my own work and the original piece]," he says. "I didn't have very many pieces at all, then I was in a faculty show at UMFA. I jokingly asked the director of the museum if she'd let me scan some of their pieces, and I thought she'd laugh me out of the building. But she was into it. So I scanned seven pieces from their permanent collection."

Rodriguez came to focus much of his "uninvited collaboration" work on the hot-button issue of immigration, specifically as it applies to the U.S./Mexico border. He cites another formative childhood experience as informing him early on about the tragic stories that surrounded the immigrant experience.

"When I was 10 years old," he recalls, "I was staying with my grandmother for the summer, and there was a lady who took care of her who was from Nicaragua. [The caretaker's] daughter had crossed over from Mexico into Arizona, and died in the desert, at 19 [years old]. I just happened to be there at that time, that exact moment that she got the call that her daughter died. She was wailing and crying. Even as a kid, I just felt for her."

Rodriguez also got an up-close-and-personal look at conditions along the border this past summer, when he worked with Battalion Search & Rescue, a humanitarian organization that searches the American deserts for lost and missing migrants. "It was important to me to be boots on the ground, even for just a tiny fraction of time, [to know] the experience of what it's like," he says. "This was in August, the hottest part of the summer. I felt the connection."

Much of the work in the salt 15 exhibition addresses that experience, directly or indirectly, including the matter of the ancient art pieces themselves crossing the border to become objects seen in an American art gallery. Another piece uses a child figure originally from a group of figures representing a family. "I'd scanned these, and right about the time I started making this work, there was this tension of children at the border [separated from their parents]," he says. It just made sense to me that I could use this child figure, in a cage, to talk about that. ... The child figure from a thousand years ago in Mexico is standing in for the child of today."

While Rodriguez acknowledges that struggling with his cultural identity was difficult, he also believes it places him in a unique position as an artist. "I come from a privileged place," he says. "I know how to navigate what I call 'the white world.' I'm showing my art in venues where most of the people are privileged, upper-middle-class, college-educated. And I see myself potentially as a bridge between the two worlds."