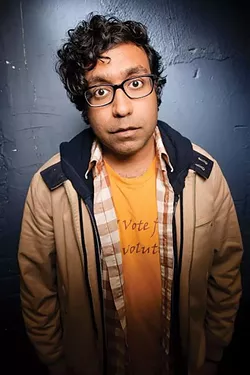

Comedian Hari Kondabolu has been making comedy out of hot-button issues like race and women's rights for more than 10 years. In addition to appearances on the late-night talk-show circuit including Jimmy Kimmel Live!, Conan and The Late Show With David Letterman, Kondabolu spent two years as a writer and correspondent for FX's Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell. His new comedy album, Mainstream American Comic, was just released last month.

City Weekly: I like to start by asking, what question have you been asked so often that as soon as you hear it, you tune out the interviewer as an idiot?

HK: [laughs] Oh my God, there's so many. Just one?

Let's start there and see what I can cross off my list.

"How do you write your material?" To me, it's like asking, "How do you think the things you think?" The only difference between me and somebody who doesn't write, is that I write the stuff down, and other people can move on with their lives.

In your online bio, there's a New York Times quote describing you as "one of the most exciting political comics in stand-up." How do you feel about that label of "political comic"?

I don't like it, but if The New York Times gives you a quote, you're going to use it. And for the purpose of branding, I understand. When some people hear "political," they're repelled by it; some people hear political, they're intrigued by it. So I get that. But for me, it's hard to call what I do "political" because to me, it's all observational. Let's say you're watching a football game. You'll have one comic talk about how ridiculous the helmets look; I might be like, "I wonder how many concussions these guys are getting. I wonder what insurance plans they have. I wonder what treatment they get after their careers." And it's not like I'm putting my "political" cap on. That's the first thing I think of, and that's just, like, years of being that person. So for me, I get why the labeling is useful, but it's not like I'm trying to do a thing. This is just who I am.

How quickly did you find your voice as a comedian when you were starting out? Was this kind of material always who you were, or did you have to get some "what's the deal with airplane food" jokes out of your system first?

No, I mean, just in the same way that human beings develop, one thing I love about stand-up is the direct correlation between your personal development and the performance, what you write about. Certainly when I was 17, 18, 19 years old, I wasn't writing jokes about racism in any real way. If anything, I was doing lots of stereotypical material about my parents, and caricatures. I really didn't know. I hadn't seen the world, I hadn't experienced anything, so I went with what I thought would work. As I became a more political figure, as my thinking changed, as I started to examine the world differently, my act started to reflect that. Certainly after 9/11, I was very different. All of us were, I think. One way that shows up in my act is I became a much more thoughtful performer. I thought about the impact of language. I thought about, what is it that I really want to talk about, what am I feeling right now, and how can I turn that into something positive? Because I feel like, for a lot of comics, that's what we do: It's a defense mechanism that allows us to recycle pain into something useful and funny for us and other people. So I really became a person who did that after that point.

So does that mean—you talk in your act about not doing impressions of your Indian parents. Did you at one point do the impression?

Absolutely I did. When I was a kid, yes. Because when you grow up, and there are no South Asian comedic role models, and there's nothing to say, "This is the way you do it ..." Not to say you mimic other comics, but at least you can see other paths to success. And when the only figure that exists on television who is South Asian is a cartoon character on The Simpsons, and you know that's effective, I've seen that be effective, obviously I'm going to gravitate to that. I'm going to see that as a comedic opportunity. If they can do it, why can't I do it? I actually have Indian parents. And honestly, it's nothing I'm particularly proud of, but I'm also aware that, every comedian when they start generally goes through a phase of figuring out what their limits are, figuring out what they want to say. And the idea of silence is paralyzing. The idea of like, maybe this doesn't work, maybe this needs another minute to set up ... you want laughter as quickly as possible. So I've had to learn to develop a thicker skin, I've had to learn to trust my instincts, that if an audience is with me, they'll be patient because they like what I've been saying. But at least initially, every comic is like, "What can I say, how quickly can I say it, and how soon will they laugh." So going along with that, I knew this stuff would work quick, doing a funny accent regardless of what I was saying.

Did you watch both political conventions?

Unfortunately, yes.

What was the balance as you watched between "I'm getting great material out of this" vs. abject horror?

[laughs] That's the perfect way of phrasing it. The part of me that's creative is thinking about ways to use this, and the part of me that's a human being is going, "What is going to happen?" I mean, with the Republican one, it's such a freak show. Even Republicans are like, "What are we doing right now?" It's, like, bizarre nationally, not even just a liberal thing. This is not the best look. And then on the Democratic side, it's the tension of, Bernie [Sanders] is there, not smiling at all. ... Like he's at his ex-girlfriend's wedding: "Ah, that was supposed to be me." But I mean, the Republican one is like, ugh, I don't even know. I thought it was hacky to joke about Donald Trump before, just because he was a pop-cultural figure. But it's not hacky to talk about him now because he might be president. It's terrifying.

Are we giving too much credit to the potential damage Donald Trump could do, or not enough credit?

Not enough. The president of the United States is not a small position, and certainly there are things that happen regardless of who is president, to some degree, things just run on their own. But there are obviously a lot of key things that the president is in charge of, and I just can't imagine that man being in charge of the whole country. Not just a piece of the country, the whole country. And obviously already we've seen the effects of what happens after he's spoken. There have been hate crimes outside of his rallies, there have been hate crimes where people yell "Trump!" while they beat people up. "Trump" is becoming shorthand for hate. And that is a very scary thing. I don't like the Hitler comparisons, because I think, you know, when you compare one historical figure to another historical figure, you completely ignore why this historical figure is doing what they're doing, and how to stop them. But I do understand the frustration of the gang mentality he engenders, the us-versus-them, the "who is the problem, who is us." Like, that stuff is scary. And it's not dog-whistling like in other elections, where he says something and you get the hint. He doesn't dog-whistle. He yells. ... It's saying "Muslims" and "Mexicans" and repeating it, and repeating it, and repeating it. And the media covering it over and over again. And Trump knows what he's doing. I'm not saying he's not an idiot, but you can be both not a really intellectual person and know how to play this particular game. And in terms of playing the media, he's a savant.

You've said that you were a Sanders supporter. Where are you on the "making peace with Hillary as the Democratic candidate" spectrum?

I mean, I'm a Sanders supporter insomuch as I believe in those values. At the end of the day, I'm a person who believes in those values more than I support a candidate. So now that Hillary is the candidate, I'm going to vote for her. I didn't even hesitate with that decision. The thing that frustrates me about the BernieBro who says "I'm not going to vote for Hillary, I'm a Bernie person ..." First of all, are you a Bernie person, or are you somebody who believes in those values. Because if you believe in those values, you have to believe that if Trump is elected, a lot more damage is going to be done. There's something about being, like, a straight white dude saying, "I'm not going to vote for Hillary, I'm going to stand by this." If Trump gets elected, women, people of color, immigrants, religious minorities, they take the hit. That's where it's scary.

You created a hashtag meme "#BobbyJindallIsSoWhite" [regarding the Indian-American governor of Louisiana]. Have you ever had any direct contact or interaction with him?

No. I've never had any personal contact. And I think he's smart enough to know a comedian—somebody who thrives off confronting things he doesn't agree with—if he engages, it's probably not a smart idea. It's not in his best interest. For me, it's great, because it opens up a whole new comedic avenue. For him, what is the point? It's weird how the internet gives people power who normally wouldn't have power: a comedian in their bedroom in Brooklyn should not have any ounce of power, but because of my tweeting, I got a story out of it. There is something great about, "Wow, I have more power than my equivalent would have 20 years ago, or even 10 years ago."

You obviously address in your comedy issues that are faced by women, gays and lesbians, and American racial and ethnic minorities other than your own. Do you feel like it's trickier, or you have to take more care with that material, even when it's ultimately supportive?

Yes, I absolutely do think that I have to take more care when I talk about other people's experiences, because they're other people's experiences. I'm making assumptions, I'm sometimes trying to put myself in their shoes based on my experience. But oppression is not a "one size fits all." It can be different based on whose experience it is, and how they're being screwed over. So as much as I can relate to a lot of things, it's not the same thing. What a woman experiences is not the same as what a man who's a person of color experiences. I might be a South Asian man, but I don't know what it feels like to be a South Asian Muslim man. There's a lot of intersections of oppression and identity that I can't relate to, so it requires me to be extra-thoughtful with my language. And if I make a mistake, and feel like I was in the wrong, to own up to it.

You did a Totally Biased segment about the Benghazi hearings, where Rand Paul mentioned an event you were involved with. How surreal was it to now be, even indirectly, a part of the Congressional record?

It was so strange. I remember being in the writers' room, and then all of the sudden I just froze, and Kamau asked me what was going on. And I said, "I think I was kind of mentioned in the Benghazi hearing a couple hours ago." I mean, no one knew what to do with that. Rand Paul decided that mentioning the fact that the State Department sent three comedians to India was newsworthy, and showed Hillary Clinton's lack of management and incompetence. What they ignored was that this has been a regular thing that every president and their administration has done: send performers to other countries. So if it was jazz musicians, would you say that's better? We send art to other countries, and it's a way of showing how our country works, how free speech works, our creativity. There's a lot of reasons we do what we do. It makes us look good. So I mean, he wasn't thinking about all that. But I think it was mostly a slap in the face at the idea of stand-up comedy being a real art form. Because I mean, if it was jazz music or Shakespeare, he wouldn't say anything. It was because it was stand-up comedy. That isn't real. We paid for clowns to go to another country? We paid this much? For clowns?

Is there still a defensiveness that comedy is a real art form?

Absolutely. I think people don't understand that. First of all, it's not just people making up random things. There's a lot of thought put into it. I don't think most people know the history of Lenny Bruce, how his journey of comedy was protecting the First Amendment and essentially dying for it. I don't think people realize the value of how comedy can spread messages very quickly, with a certain immediacy that maybe a play or a book or a movie or TV show cannot do. And the fact that it's affordable. Why is only art if its' expensive and inaccessible? Art is also words, art is ideas, and art is a performance with just a human being. Which is traditionally how it has worked—long before we had the ability to make sets, there were people telling stories. So I mean, it really devalues it. There's the idea of, "I could do that, it's just a person and a microphone." Which is ridiculous, because people do magic, and I can't do magic. David Blaine does magic; he doesn't use anything besides maybe a deck of cards, but I can't do that. I don't assume I can do that.

You're working on a documentary for TruTV about Apu from The Simpsons. When do you first remember becoming aware of the character, and how did it affect you?

I was a Simpsons fan from the beginning, even The Tracey Ullman Show days when it was just a small little sketch they did. So when The Simpsons came out, my parents allowed me to see it, and I loved it. As soon as Apu was introduced, I was familiar with him, but I didn't see him as upsetting. If anything, I was just happy that we [South Asians] got to exist. Like, we weren't given a chance to exist in popular culture until Apu showed up. It wasn't until much later, when I realized that this was how we were going to be seen in a broad, mainstream way, that I thought it was upsetting. Up to that point, I didn't have any issue with it. And to be honest, it was tricky to be frustrated by him as a character, and still find him funny and thoughtful—to love that show and still feel like it was the result of some negativity.

On Mainstream American Comic, you refer to the demographics of Portland [where it was recorded], which might be comparable with Salt Lake City. Do you find there's a different vibe in crowds where it's mostly white liberals?

I don't know Salt Lake City very well. I mean, I know there's an incredible counter-culture which I've heard about for years now. But it's not like every audience is the same. There's a difference between an NPR white liberal and an organizer/activist. And I get both of those groups, in addition to your standard comedy-club crowd. I mean, I'm a comedian who's on TV. I'm on Comedy Central fairly regularly, and late-night shows. So I have to play to both. I will say that I have found, the more diverse the crowd is, the better it's going to be, because it allows everyone to share a space and laugh together, as opposed to, "Am I allowed to laugh at this?" I don't know how I feel about this. I don't have this experience. I don't know anyone who has this experience." But if a crowd's excited, it's not going to matter, to some degree. If they're willing to listen, willing to be challenged, I'll be fine.