How does a lawmaker get educated on a bill? Perhaps more importantly, how should a lawmaker learn the pros and cons of a bill before casting a vote?

The questions carry particular heft in Utah’s part-time, citizen Legislature. Harried legislators spend less than two months in session each year and are devoting more of their time to interim committee work the rest of the year. Utah is one of only six states to function under a strictly part-time legislature, according to Bruce Feustel, senior fellow with the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) in Denver. California, New York, Michigan and Pennsylvania have full-time legislatures. The remaining states fall somewhere in between.

Utah lawmakers often cite their “layperson” role in explaining the rushed debate and controversial votes that can anger constituents. They reason that limited time, combined with their need to make a living in the real world, require them to rely heavily on lobbyists and to vote with less than ideal information.

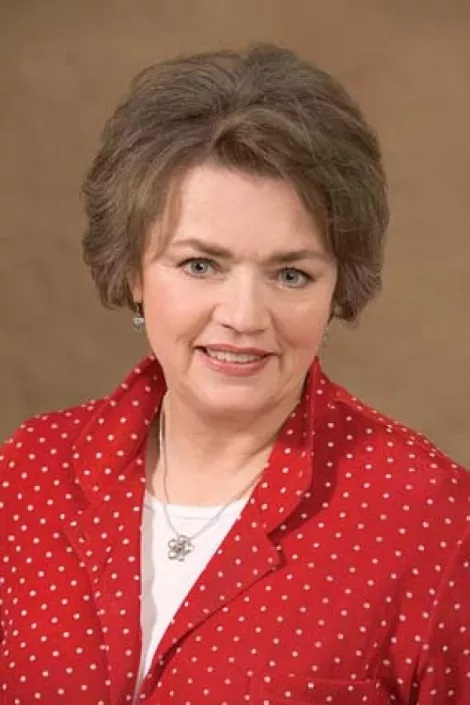

Consider the case of Sen. Margaret Dayton, R-Orem. On Feb. 21, Dayton convinced two other colleagues on the Senate Education Committee to kill a bill marking $300,000 for the accelerated learning program, International Baccalaureate. Dayton objected on the grounds that IB is too closely aligned with the goals of the United Nations.

She had never been to an IB class, nor had the other two opponents. One week later, after substantial public uproar, legislative leaders found $100,000 for IB.

In an e-mail to angry citizens who had contacted her, Dayton offered an explanation for her vote, which included “…We are a lay legislature with varying areas of experience and expertise. … I’m guessing that most legislators who voted for HB266 (the IB bill) have not attended an IB Class. By way of information, I was also asked to vote on a mine safety bill for coal mines; I have never been in a coal mine. I have been asked to vote on

numerous bills regarding divorce issues, and I have never been divorced. … The point is part-time lay legislators cannot make a field trip on every issue; we do as many as we can, but we cannot do them all. If there are issues regarding IB presented during the interim, I will do my best to have some meaningful time for this discussion.”

It’s tough to do the homework, but legislators still owe it to voters to learn what they can about a particular measure, says NCSL fellow Feustel. “Constituents expect their representatives to get to the bottom of an issue. “[Legislators] should push for the most information they need to be comfortable with an issue.”

That may mean relying on other committee members with expertise in a certain field or occupation. And while lobbyists typically have a tarnished reputation with the public, they aren’t all bad. “Part of dealing with lobbyists is making sure when they promote a bill that they can articulate fairly and adequately the other side,” Feustel says.

Sen. Darin Peterson, R-Nephi, initially voted with Dayton to kill the IB bill. Though busy as the rest, a few days later he visited an IB history class at Salt Lake City’s West High School and listened to a discussion about the Hungarian Revolution of 1958. Peterson has decided to support the funding.

Sen. Greg Bell, R-Fruit Heights, says when weighing a vote, he tries to contact every stakeholder in a bill, especially those he knows will be controversial. “I call all I know who have a stake in a bill. Others come forth as the word gets around. After taking input, I make a decision whether to go forward with a bill or not. I do my best to get a consensus between responsible stakeholders and then make a decision.”

Peterson finds some grace in legislative rules that allow the changing of one’s mind.

“Our rules allow us opportunities to rehear or change directions with any piece of legislation,” he says. “We have the nicety of stopping something procedurally so we can do what our study and conscience dictates.

“Occasionally the public views these [procedures] as being silly or leading to stupid or uninformed action. But I’d gladly take many public criticisms to get to one right decision.”