Page 2 of 3

ON THE ROAD

If the date is right and the organizing effort is effective, there’s no reason that Occupy couldn’t get close to a million people into the nation’s capital for an economic-justice march and rally.

That, combined with teach-ins, events and days of action across the country, could kick off a new stage of a movement that has the greatest potential in a generation or more to change the direction of American politics.

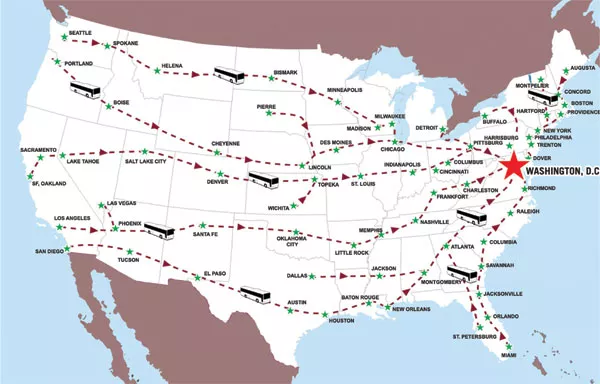

Occupy groups from around the country could travel together in zig-zagging paths to the capital, stopping and rallying in—indeed, Occupying!—every major city in the country along the way.

It could begin a week or more before the conference, along the coasts and the northern and southern borders: San Francisco and Savannah, Ga.; Los Angeles and New York City; Seattle and Miami; Chicago and El Paso, Texas; Billings, Mont., and New Orleans—Portland, Ore., and Portland, Maine.

At each stop, participants would gather in that city’s central plaza or another significant area with their tents and supplies, stage a rally and general assembly, and peacefully occupy for a night. Then they would break camp in the morning, travel to the next city and do it all over again.

Along the way, the movement would attract international media attention and new participants. The caravans could also begin the work of writing the convention platform, dividing the many tasks up into regional working groups that could work on solutions and new structures in the encampments or on the road.

At each stop, the caravan would assert the right to assemble for the night at the place of its choosing, without seeking permits or submitting to any higher authorities. And at the end of that journey, the various caravans could converge on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., set up a massive tent city with infrastructure needed to maintain it for a week or so, and assert the right to stay there until the job was done.

The final document would probably need to be hammered out in a convention hall with delegates from each of the participating cities, and those delegates could confer with their constituencies according to whatever procedures they prescribe. This and many of the details would need to be developed over the spring.

But the Occupy movement has already started this conversation and developed the mechanisms for self-governance. It may be messy and contentious and probably even seem doomed at times, but that’s always the case with grass-roots organizations that lack top-down structures.

Proposals will range from the eminently reasonable (asking Congress to end corporate personhood) to the seemingly crazy (rewriting the entire U.S. Constitution). But an Occupy platform will have value no matter what it says. We’re not fond of quoting Milton Friedman, the late right-wing economist, but he had a remarkable statement about the value of bold ideas:

“It is worth discussing radical changes, not in the expectation that they will be adopted promptly, but for two other reasons. One is to construct an ideal goal, so that incremental changes can be judged by whether they move the institutional structure toward or away from that ideal. The other reason is very different. It is so that if a crisis requiring or facilitating radical change does arrive, alternatives will be available that have been carefully developed and fully explored.”

After the delegates in the convention hall have approved the document, they could present it to the larger encampment—and use it as the basis for a massive rally on the final day. Then the occupiers can go back home—where the real work will begin.

WASHINGTON’S BEEN OCCUPIED BEFORE

The history of social movements in this country offers some important lessons for Occupy.

The notion of direct action—of in-your-face demonstrations designed to force injustice onto the national stage, sometimes involving occupying public space—has long been a part of protest politics in this country. In fact, in the depth of the Great Depression, more than 40,000 former soldiers occupied a marsh on the edge of Washington, D.C., created a self-sustaining campground and demanded that bonus money promised at the end of World War I be paid out immediately.

The so-called Bonus Army attracted tremendous national attention before General Douglas Macarthur, assisted by Major George Patton and Major Dwight Eisenhower, used active-duty troops to roust the occupiers.

The Freedom Rides of the early 1960s showed the spirit of independence and democratic direct action. Raymond Arsenault, a professor at the University of South Florida, brilliantly outlines the story of the early civil-rights actions in the 2007 book Freedom Rides: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.

Arsenault notes that the rides were not popular with what was then the mainstream of the civil-rights movement—no less a leader than Thurgood Marshall thought the idea of a mixed group of black and white people riding buses together through the deep South was dangerous and could lead to a political backlash. The riders were denounced as “agitators” and initially were isolated.

The first Freedom Ride, in May 1961, left Washington, D.C., but never reached its destination of New Orleans; the bus was surrounded by angry mobs in Birmingham, Ala., and the drivers refused to continue.

But soon other rides rose up spontaneously, and in the end there were more than 60, with 430 riders. Writes Arsenault:

“Deliberately provoking a crisis of authority, the Riders challenged federal officials to enforce the law and uphold the constitutional right to travel without being subjected to degrading and humiliating racial restrictions. ... None of the obstacles placed in their path—not widespread censure, not political and financial pressure, not arrest and imprisonment, not even the threat of death—seemed to weaken their commitment to nonviolent struggle. On the contrary, the hardships and suffering imposed upon them appeared to stiffen their resolve.”

The Occupy movement has already shown similar resolve—and the police batons, tear gas, pepper spray and rubber bullets have only given the movement more energy and determination.

David S. Meyer, a professor at U.C. Irvine and an expert on the history of political movements, notes that the civil-rights movement went in different directions after the Freedom Rides and the March on Washington. Some wanted to continue direct action; some wanted to continue the fight in the court system and push Congress to adopt civil-rights laws; some thought the best tactic was to work to elect African Americans to local, state and federal office.

Actually, all of those things were necessary—and Occupy will need to work on a multitude of levels, as well, and with a diversity of tactics.

There’s an unavoidable dilemma here for this wonderfully anarchic movement: The larger it gets— the more it develops the ability to demand and win reforms—the more it will need structure and organization. And the more that happens, the further Occupy will move from its original leaderless experiment in true grass-roots democracy.

But these are the problems a movement wants to have—dealing with growth and expanding influence is a lot more pleasant than realizing (as a lot of traditional progressive political groups have) that you aren’t getting anywhere.

All of the discussions around the next step for Occupy are taking place in the context of a presidential election that will also likely change the makeup of Congress. That’s an opportunity—and a challenge. As Meyer notes, “Social movements often dissipate in election years, when money and energy goes into electoral campaigns.” At the same time, Occupy has already influenced the national debate—and that can continue through the election season, even if (as is likely) neither of the major party candidates is talking seriously about economic justice.

That’s why a formal platform could be so useful—candidates from President Obama to members of Congress can be presented with the proposals, and judged on their response.

The important thing is to let this genie out of the bottle, to move Occupy into the next level of politics, to use a convention, rally and national event to reassert the power of the people to control our political and economic institutions—and to change or abolish them as we see fit.%uFFFD

This story originally appeared in the San Francisco Bay Guardian.