“I’ve been told to tell you that you are not welcome,” one of the men said to Barlow.

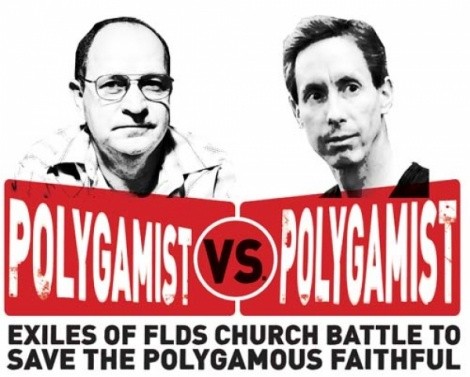

Barlow was among the first of what would be more than 200 men and 1,000 male youths banished by FLDS Prophet Warren Jeffs. Jeffs led the church from 2002-07 before his arrest in September 2007 on two counts of rape as an accomplice, charges for which he was subsequently convicted and is currently serving two consecutive sentences of five years-to-life in the Utah State Prison.

After being barred from the church, Barlow went home to the two-story, seven-bedroom house in Hildale, Utah, he’d built with his two wives, Joan and Shirlee, and told them what had happened. Joan started laughing, hoping it meant they could leave the FLDS community that she considered repressive.

The children were less pleased. When they left the church after the service, the congregation parted and turned their backs toward the Barlow offspring, as if they were lepers.

The news was hardly unexpected. Jethro, an accountant for 30 years who had been instrumental in building the FLDS community, had been on a Jeffs’ memo listing men in the community whose priesthood authority was in question. Without that authority, according to FLDS beliefs, he would be unable to take his wives to the celestial kingdom. “I kind of figured I had to get myself there,” Joan jokes.

Unlike most of those whom Warren Jeffs kicked out of his church and town, Jethro left the community with his two wives and most of his children—only five adult children stayed. To this day, the estrangement of those five, whom Jeffs assigned to one of Jethro’s brothers as their new father, is hard for Jethro and first wife, Joan, to discuss. A justice of the peace married Jethro and Joan in 1974, when he was 22 and she was 15.

“I don’t know if I can,” Joan says, when asked to speak about her five estranged children, trying several times before trailing into a painful, throat-thickened silence.

For two years, the Barlows struggled to find work and a new home. Then, in May 2005, Jethro Barlow was hired as a consultant to Salt Lake City-based accountant Bruce Wisan, the court-appointed special fiduciary for the United Effort Plan Trust.

The trust, with assets of more than $110 million, owns 85 percent of the land and housing built, often during Saturday work projects, by the FLDS community in the polygamous twin townships of Hildale and Colorado City. Wisan took over after UEP trustees refused to defend the trust from several lawsuits, leaving the town’s residents vulnerable to mass evictions if the lawsuits were lost.

After Wisan hired Jethro Barlow, Jethro petitioned the trust to allow his family to move back into their former home, a mostly unfurnished property that even four years later Jethro admits still doesn’t feel like a home.

Jethro and a fellow exiled FLDS member, Isaac Wyler, represent Wisan and the UEP advisory board—made up of mostly ex-FLDS members—in what they initially thought would be an effort of “rescuing a distressed trust.” In the past year and a half, however, that rescue has become a vicious fight between the trust and its former administrators—the FLDS Church—over the lives and rights of the people who live there. That fight has come to a head in what Jethro calls a test case, namely a civil-rights complaint filed by severely disabled Ron Cooke. The ex-FLDS member says his life is being put in daily jeopardy by the FLDS-staffed municipal government’s refusal to acknowledge his right to live there.

Despite what amounts to a highly wrought divorce between the FLDS and the trust, Jethro wants to build bridges, not burn them. He still lives as a polygamist and still is, as he wrote in a court document, “a staunch believer in the fundamental rights of our religious community.”

Wife Joan says, “Part of him hasn’t let go of the good old days.” It’s as if he wants to show his estranged children—along with the rank-and-file FLDS members he empathizes with—that he cares for them and is trying to help them. Bottom line: Jethro wants Hildale-Colorado City to turn into a real town. “Until I see a vibrant, local economy and happy children and young people growing up with a vision of fitting into this community, only then will I be content,” he says.

Red Sand In Your Veins

Jethro

Barlow is a cautious, erudite man with a dry wit and a fierce pride in

his Mormon fundamentalism and polygamous heritage. Even though he feels

his is “a voice howling in the wilderness,” he has largely avoided the

public limelight.

But after FLDS spokesman Willie Jessop characterized anyone associated with the UEP as, Jethro says, “enemies of the community,” a deeply offended Jethro decided to speak up. “The idea I would compromise the stability of my own children there is totally foreign,” he says.

Neither Willie Jessop nor any representative from the FLDS Church returned calls for comment made to FLDS Church attorney, Rod Parker.

That lack of balance comes from the FLDS Church’s current administration being what Jethro calls “a Ponzi scheme where promises are made of housing, wives and salvation that outrun their ability to deliver.” The distractions it uses include filing “dozens of vexatious, shallow, frivolous lawsuits, then going to the media to complain about the [UEP] lawyers.”

Utah Assistant Attorney General Tim Bodily estimates the trust and the church have spent more than $1 million on attorneys since May 2008—an “absolutely obscene” number. All of this could have been avoided from the get-go, he says, if the FLDS had shown up in court from Day 1 instead of waiting until the May 2008 raid on Yearning for Zion—the FLDS compound in Eldorado, Texas—to decide it wanted its townships back.

The night after the raid, many former Hildale-Colorado City residents allegedly chosen by Warren Jeffs to populate his self-proclaimed holy land returned to the Arizona-Utah strip. “The next day we began seeing Texas plates,” Isaac Wyler recalls. “They drove all night.”

But when they returned, they found the houses and land were now occupied by some of the 300 former FLDS members who had petitioned the trust for homes. The UEP had placed between 50 and 100 nonbelievers—all with personal history, financial and sweat equity invested in the building of the townships—in trust properties.

Moving to the townships can be an attractive proposition. The UEP only charges a $100 monthly occupancy fee and enforces a property tax payment. Despite the UEP- FLDS tension, many of those who have returned also cite the peaceful, small-town atmosphere as another reason.

If you have “red sands in your veins,” Jethro says, there will always be a “welcome home” from the UEP. Part of that welcome includes the UEP’s anticipation that occupants will eventually buy their discounted homes from the trust—which, if successful, would mean that Jethro Barlow is helping bring about the dissolution of the trust, which he worked so hard to build before Jeffs threw him out.

That long-term plan puts the trust in the crosshairs of a religious institution that, Bodily says, only wants true believers as neighbors.

Bodily describes the situation as “a very awkward conflict.” Choose the FLDS, and you’re endorsing their religion. If you support the trust, then you’re endorsing the secularization of a community—not, he acknowledges, that Jethro and Wyler would see it that way. “They would say they’re simply trying to empower individuals to make their choices.” Indeed, Jethro says the UEP is “attempting to bring fairness into the picture, so people who contributed to [the trust] can direct where their property goes.”

But if individual choice must defer to the communal good—as is the case with the FLDS Church—then such empowerment equates as a challenge to church authority.

Bodily says the Attorney General’s Office has to give equal weight to the interests of the FLDS and nonmember residents. However, he adds, whatever Jethro and Wyler are doing, “It’s fair to say it’s not working.”

Non-FLDS residents question Utah Attorney General Mark Shurtleff’s neutrality, citing his office’s settlement proposal to create a subdivision of 50-acre lots on the outskirts of Hildale-Colorado City for non-FLDS UEP occupants. Jethro, for one, says the proposal, which was rejected by 3rd District Court Judge Denise Lindberg, was “really disappointing.” He fears that such legal overtures only strengthen the will of the FLDS to resist the UEP.

Resident Genevive Hainline knows how resolute the FLDS can be. Her mother, Cora Lee Witt, allegedly was thrown out of her UEP home in 1981 by the FLDS Church, along with Hainline, then age 1. Now a mother of three small children herself, Hainline fought for eight months to get electricity to a rundown UEP house she’s remodeling. For several months, local FLDS cops often questioned her when she worked in her backyard. She’s also endured harassment from a neighbor who claims a garage on her lot.

The Informer

Jethro

Barlow was born in 1952 into the equivalent of polygamous royal blood.

His father, Joseph, was an ordained patriarch of the community, a town

council member and leading businessman, with four wives and 60 children.

Jethro was his father’s right-hand man, working with him on dozens of family businesses. He was also deeply involved with the United Effort Plan Trust, an organization set up in 1942 to bank land donated by FLDS members, on which followers could build houses with community help and without resorting to debt.

In 1990, then-Prophet Rulon Jeffs gave Jethro his second wife, 20-year-old Shirlee Cooke. They met on a Monday and were married by Thursday. To her surprise, she says, “I fell head over heels in love.”

An FLDS insider, Jethro was increasingly horrified by the authoritarian administration of the Jeffs, Rulon and Warren. Rulon, he says, introduced elitism and began condemning entire families for having immoral bloodlines.

After Rulon had a stroke, control issues under his son Warren worsened. Shirlee found she couldn’t talk to her mother or her sisters freely anymore. “It ruined my relationship with them.” Joan’s brothers stopped talking to her, as did most of the family’s friends.

Jethro believes Warren Jeffs wanted to make an example of a senior community figure in the community. What Jethro thinks finally marked him for expulsion was telling a tax client in the summer of 2002 that terminally ill Rulon Jeffs would die soon, flatly contradicting Warren Jeffs’ preaching that his father would live forever. The client told the prophet of Jethro’s prediction, and Jeffs scolded Jethro.

After Rulon Jeffs died in September 2002, Jethro could not get an audience with Warren, the new prophet. In January 2003, the list of questioned members went around the community, and a month later, as Isaac Wyler puts it, Jethro, along with Canadian FLDS leader Winston Blackmore, were “publicly executed.”

Free At Last

Before Jethro closed up shop, clients picked up their tax returns. “People couldn’t get over it,” Joan recalls. “It was like having a funeral before you died.”

Jethro’s biggest loss was his father. He went from being Dad to someone trying as hard as he could to conform to Jeffs’ newly approved gospel, which meant forsaking his son. “I never had a conversation with him that wasn’t scripted from that day on,” Jethro says. “I never felt our souls touching in communication, as we had for so many years before.”

Jethro’s

expulsion, Joan says, “sent him into a slump so deep and dark it scared

me.” Jethro admits, “I still haven’t got over it. I was the most

steeped and hard-boiled [in the FLDS culture]. I was born into it.”

The wives did not share the frustrations of their husband, however. Joan welcomed the escape, and when Jethro and Shirlee drove out of the town, Shirlee screamed, at the top of her lungs, “Freeeee-dom!” They moved to Holbrook, Ariz., the first of seven rental moves, where the children attended a school with African- American and American Indian students. When Jethro went to a parent-teacher conference, he struggled to explain his having two boys that were six months apart. They hid their polygamy as best they could, Jethro taking Joan regularly to a Chinese restaurant, while his dinner dates with Shirlee were at a Pizza Hut.

When Wisan came knocking two years later, Jethro was grateful for a job. At first, he thought FLDS residents would see the new trust management as bringing relief. But Warren Jeffs, even as a fugitive from the law, politically outmaneuvered them by instructing his flock to “do nothing, say nothing.”

That included not paying property taxes in 2006. When the trust’s Wyler knocked on doors for information about who lived there, the silent treatment was, Jethro says, “an effective way to limit the fiduciary’s ability to function.”

Rejected by the Lord

Spend

only a few hours with Wyler, Jethro’s point man, on the townships’

mostly unpaved streets, and you come face-to-face with FLDS resistance

to the UEP.

As dusk settles on Colorado City one late October afternoon, silence reigns, broken only by a cow’s lowing and the rap of Wyler’s right hand against a trailer’s front door.

“I think even my knuckles have calluses on them,” the horse-farm owner says with a booming laugh.

He raps out a three-knock coda, repeats it twice more. There’s no answer, so he tapes a delinquent tax notice to the door.

For the past couple of years, Andrew Chatwin has videotaped Wyler’s every move each time he’s stepped on one of the UEP’s 800 properties, 600 of which FLDS members live in. “They’ve accused him of everything— of trying to run over old ladies, breaking into houses, vandalism,” Chatwin says.

“How do you get that kind of hatred installed in a kid that young?” ISAAC WYLER wonders. “That takes some serious brainwashing.”

In July 2009, Wyler was convicted of criminal trespass by a Mocassin, Ariz., justice court judge, and sentenced to two years probation and fined $400. The sentence is being appealed, but after Wyler’s conviction, Colorado City charged Jethro and Wisan with related crimes.

Wyler parks his truck by a large, woodfronted house. It had been vacant for six years, he says, as he fishes out a key from a plastic jar full of keys. When he entered the property for the first time, he found cats and pigeons. He changed the locks, and a couple who signed an occupancy agreement moved in. Even though they found the remodeling project too big and moved out, their possessions were still supposed to be there and the occupancy agreement was still in effect. Wyler, however, heard a rumor that the FLDS family who once lived there had changed the locks and “threw [the UEP-approved couple’s] stuff away.” He was checking to see if this was true.

While Wyler waits for the local police he’s requested to witness his investigation, a dark-blue SUV parks close to Wyler’s truck. The driver, Penny Barlow—not directly related to Jethro Barlow—remains in the car, studiously ignoring Wyler and Chatwin as she talks on her cell phone. It was she and her husband, Chatwin says, who allegedly moved in the week prior without permission of the courts or the fiduciary.

When a Colorado City police truck arrives, Penny Barlow, a slender woman in an anklelength purple dress, her hair swept back in a wave, gets out. As everyone watches, Wyler tries his key. It doesn’t work. Wyler believes Penny Barlow has changed the locks.

Penny Barlow started building the house in 1991 with her husband. She says that the FLDS Church gave them “the land to improve upon it. We put in the footings, the building, everything here that you see.” When they needed a larger place, they moved up the road. Now, in addition to their current home, the FLDS Church—in what Wyler considers an obstructionist move—is directing Penny and her husband to reclaim their old house.

Asked how long the house has been empty, she smirks and says, “It’s a matter of debate.”

Wyler says six years. “You can do the math as good as I can,” she replies curtly.

Penny Barlow did not go to Texas, she says. Wyler chips in, “She’s one of the ones who got rejected by the Lord,” referring to recorded statements by Warren Jeffs that those not invited to Texas were disowned by God. Penny Barlow appears startled, accusing Wyler of getting the information from “illegally obtained records.” Finally, she says, “I don’t feel very rejected, actually.”

The UEP trust had been taken from her church after “false accusations were made,” she says. Under Wisan, she sees its assets being dissipated “and our just wants and needs are having a very hard time being met.” The land and its harvests “have been basically stolen from us.”

Private ownership of the land, as envisioned by the UEP, she says, is “not the way we were understood to settle here.” Her cell phone rings, she answers it, and then she politely asks the UEP men and the reporter to leave. Boys dressed as cowboys, several on miniature ponies, watch from the corner. One of them suddenly gallops over as Wyler backs out onto the street. He stares at the truck’s occupants as he circles behind it—as if challenging the UEP employees—or driving them out. It’s a grinding glare that Wyler’s gotten used to.

“How do you get that kind of hatred installed in a kid that young?” he wonders. “That takes some serious brainwashing.”

Wyler’s irritated with Penny Barlow.

“What right does she have to come and get that second house without permission and drive the people who were there out?” he asks. And while Penny Barlow cried foul about FLDS members discovering their home locks were changed by the trust while they were at work, the reality, in this case, Wyler says, is the opposite.

Hook Me Up

A window is broken and the rat-bitten corpses of dismembered pigeons litter the floors. The pigeons fly in through the broken window, get trapped and die. The house’s builder, Jethro says, “claims an interest in it but refuses to do anything with it.”

Casualties other than wasted assets include non- and ex-FLDS residents who moved in at the UEP’s invitation, only to be met, after the YFZ raid, with determined opposition. The most disturbing example is Ron Cooke.

Cooke has idyllic memories of, as a FLDS teen, hiking for days in the striking Vermillion Cliffs that cradle the polygamous townships. When he was 18, he left and worked in construction. While laying pipe on a Phoenix main street three years ago, he was hit by a truck and spent four weeks on life support with spinal and brain injuries.

“Ron’s many years of service, his bloodline and his special handicap needs moved them to the head of the class,” Jethro says, when it came to assessing their right to occupy a UEP property. That, however, “put them in a position where they are at the grinding point of the resistance the city is putting up to the trust.” So, for 18 months, Ron has been forced to live in a cramped trailer built to transport four-wheelers, one he initially thought would be their home for just a few weeks. “He was slowly getting better before we moved here, but emotionally, he’s gone backward,” Jinjer says.

The home’s original builder was granted prepaid utility hook-ups in a 2001 building permit signed by city officials. But the city told the Cookes that the permit had expired, even though, as Jinjer points out, many unfinished properties in the townships still receive power and water. “They took no notice of it anywhere else, but us, they enforce,” she says.

Ron hand-delivered a letter to Hildale Mayor David Zitting in October 2008 but got no response. So, in December 2008, he filed a housing-discrimination complaint with the Arizona Attorney General’s civilrights division against Hildale-Colorado City Utilities. Ron alleged that the city’s “claims that I need new plans, permits and inspections” to obtain hook-ups are excuses to hide “housing discrimination,” because he is non-FLDS. He also claims the city has failed “to make reasonable accommodation for my disabilities.”

Ron sleeps with a battery-powered oxygen machine to help him breathe. Without it, he could die. They keep a generator running as a backup, costing them $200 a week in gas. After a year and a half of fighting for hookups, Jinjer says, they are “super-broke.”

It’s not just about money. Outside their trailer, the wind picks up, hurling waves of red sand through the air. The Cookes used their shower in the trailer so much that the base cracked, forcing Jinger to shower her disabled husband outside at night in the cold, so he could go to bed clean. “I couldn’t believe I was doing it,” she says.

At a conciliation meeting in early October 2009 in Phoenix between officials from the Arizona Attorney General’s Office and Hildale-Colorado City authorities, with the Cookes and Jethro Barlow on the telephone, an agreement was reached that the Cookes would receive power. Two weeks later, the city did an about-face and gave the permit to the man who built the home and who had abruptly reemerged to claim the property.

When the outraged Cookes demanded to know why they weren’t given the permit, Jinger says, “They told us, ‘We thought you weren’t interested.’” While Jethro is certain the Cookes will eventually receive utilities, he describes Hildale-Colorado City’s treatment of Ron as “reckless disregard for human life. The city has contrived the flimsiest, worst, mostdisingenuous reasons for not serving this family.” Colorado City’s town manager, David Darger, declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

Only Plygs Allowed

Joan

and Jethro Barlow are having breakfast with Isaac Wyler in the

Centennial Parkowned eatery, Merry Wives. She says she often ribs her

husband about why he does a job that makes so many people hate him.

“Somebody has to stand up and do it,” Wyler interjects.

An high school English teacher, Joan feels askew in a township she contrasts to Baghdad. “I don’t enjoy going where I’m not wanted,” she says, so she’ll shop at a St. George Walmart rather than the local grocery store. “It’s like we’re at war, yet we’re not.” Nevertheless, her husband, she says, “feels like this is where he belongs.”

Jethro sticks to his polygamous beliefs and to his desire to be part of the community that, currently, is stridently opposed to him. His wives, however, both say they would discourage their children from entering polygamy. Jethro wants to see a return to the days when an Air Force traveling band would perform for the community, when a talent show by local adolescents would bring FLDS and non-FLDS together. “I never spent any more time in anywhere that felt like home.”

He sees hopeful signs of change. The FLDS Church is holding church meetings after years of them being banned by Warren Jeffs. Church members are working on their homes and Mohave Community College now boasts 100 FLDS students.

While the FLDS Church is calling on Utah’s courts to vacate the reformation of the trust and remove Wisan, Jethro hopes the leadership will “accept reality” and negotiate with the trust, perhaps, he says, over a few beers.

He wishes

the FLDS would live its religion. “There’s nothing in it that justifies

the treatment they’re dishing out to people who don’t believe.”