Page 2 of 2

A RUN FOR HER LIFE

Eighteen months after Annie Macdonald buried her 5-year-old daughter in late 2003 in the Farmington cemetery, a woman approached her at her LDS ward and asked her if she wanted to join her and some friends in a run. Annie had long relied on solitary running as a physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual outlet. It had also aided her in processing a terrible accident in 1999, when her toddler daughter Kailee got caught in a tree swing and nearly hanged herself. Until her death four years later, Kailee was severely disabled.

Annie joined the group as they ran through leafy Farmington, up past Lagoon amusement park and into the surrounding hills, where they could look down at the animal enclosures and rides. "I remember at the end of it thinking, 'This is home, this is good,'" she says. Running was "the breaking point," she says, in dealing with her grief. She resolved to live life to the fullest and honor her daughter's memory.

Several of the women asked her if she wanted to do the Wasatch Back relay with them. Two of them were the mother and wife of Tanner Bell, co-founder of the Ragnar Relay Series. "Doing my first Ragnar was so inspirational and made me feel like I could do anything," Annie says.

Fast-forward nine years through a multitude of Ragnar relays, and Annie decided to embark on a unique running adventure. One rain-swept Saturday morning in mid-May, 2015, she gathered with family and friends in the small, picturesque Pleasant Green cemetery overlooking Magna and the Salt Lake Valley, where her ancestors are buried—including descendents of the first Italians to convert to Mormonism in the 1850s.

Cheers erupted as Annie—her thick, black, long wavy hair pulled up in a pony tail—set off with her sister Reese Pahl and several relatives to run one mile in the Salt Lake Valley for each year of her life.

She and Pahl grew up on a 110-acre farm, back when Magna and the surrounding area were predominantly rural. Their marathon-runner parents routinely signed up their six children for half-marathons—Annie loved it, but her sister, Pahl, hated it. As she left home, she says, she vowed never to run again.

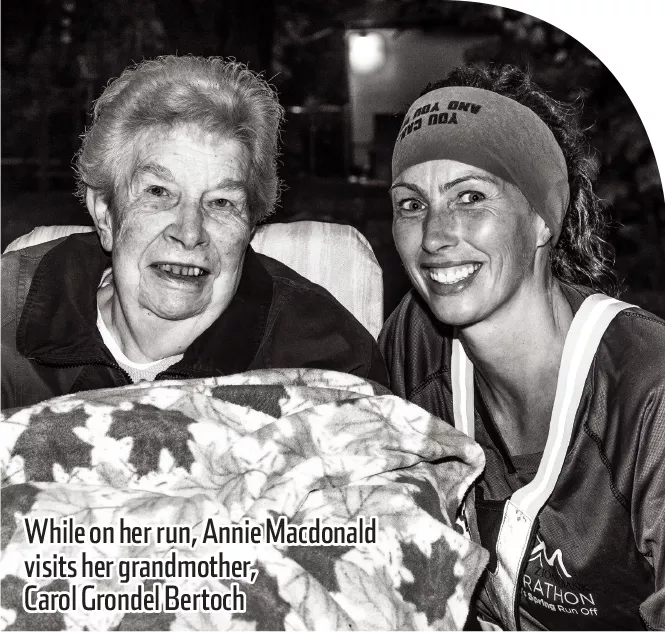

They ran down the middle of 3500 South, which in the pre-dawn hours, was all but empty of traffic. Their route took them past the house of their 90-year-old grandmother, who awaited them on her covered porch to cheer them on in the rain. Pahl thought about how, when her grandmother was in labor back in the 1940s, 3500 South had been a dirt track and she had to be transported to the hospital in a sleigh.

Annie and her small entourage turned left onto 5600 West, passing a fast-food restaurant where she had her first job at age 14.

Along 5600 West, what had once been their playground of farms, barns and fields, was now home to WalMart, Del Taco and Discount Tire. As they ran, the darkness turned the darkest shade of blue, before the sun rose, barely peeking through the rain clouds.

Annie collects objects on her runs. She picked up a small ceramic heart, scratched and broken, along with beaten and marked pennies. When she stopped to pick up a Barbie doll's leg, Pahl had enough of her younger sister's ways. "Don't," she snapped.

They crossed 2100 South, soaked to the bone. Shortly after, Annie's husband of one year, Brad, joined them. Brad is a fellow runner, although without Annie's love of the sport. They turned off 5600 West, going up 700 South towards Redwood Road and met one of Annie's friends, who had run 10 miles from Bingham High School, to symbolically connect her to her old school days. On the corner of Redwood Road and 400 South, they shot off a confetti cannon to mark the encounter.

Puzzled passersby called out, "What are you doing?"

Rain-drenched blankets were stretched out on the Interstate 15 underpass, their owners panhandling at the intersection below. "Can you imagine having to sleep on concrete?" Brad said to his wife.

A homeless man called out to them, "You guys are wack-wack."

They ran past the Copper Onion—the restaurant where Annie and Brad had their first date—turned up 200 East to 100 South, then turned left. Annie glanced to her right; she had chosen this part of the route because, for four years, she and Kailee had travelled that street three or four times every week on their way to Primary Children's Hospital, before Kailee's respiratory system began to shut down.

When the accident occurred, Kailee had been playing with her cousins on the swing in Pahl's garden. Pahl went inside to answer the phone. Annie never blamed Pahl for what happened—and Pahl, like her sister, had found in running a way of processing her feelings. "It was a super-hard time for me," Pahl says. "I felt like I was the one who ended her life." The sisters grew closer through running together.

Pahl thought it irreverent to their Mormon faith to run up Main Street through Temple Square, but followed her sister. Annie had been excommunicated in her early 20s because, after her first divorce, she had had sex outside of marriage. That expulsion—and her daughter's horrific accident—left Annie angry at both her God and her church. To be re-baptized required a genuine commitment on her part, but first she had to find out if she actually wanted to remain in the LDS Church. "I'm going to dig to find out if I believe this," she said.

She gave up running during her first marriage, but in the years following her daughter's accident, she returned to it with a vengeance. "I had nights on my runs—I was screaming, swearing at God, I was absolutely angry," she says.

But, after reconciling herself with God, she regained her church membership.

Annie and Pahl ran up Capitol Hill, where they were met by their youngest sister, bringing them PB&J sandwiches. Annie pointed out an apartment near the Capitol where she once lived, then set out on a four-mile trail run close to Ensign Peak. It was like a secret trail, Annie thought, as she ascended almost up into the clouds. "It was away from everything. The clouds felt like we were alone, out there by ourselves."

Annie knew that the Davis County section of her run would be emotional. As they ran down into Bountiful, Pahl told her she couldn't go on. The rain and the cold had gotten into her bones to the point she couldn't pull her gloves off. The sisters hugged and parted, Pahl having accompanied Annie farther than anyone else on her run.

Annie was joined by a married couple of runner-friends who wore costumes in tribute to her love of costumed running: He wore a buffalo hat and brightly colored socks; and she, a boa, cat-hat and tutu.

Annie ran by the home where she cared for Kailee in the last years before her death. The group fell silent as she pointed out her daughter's bedroom window. They ran past the LDS ward house where Kailee's funeral was held. Annie recalled that 350 people attended the funeral, showing that, even though her daughter had been unable to communicate after the accident, she had touched many lives.

The last leg of Annie's "sentimental journey" was from Kailee's grave to her home, a distance of 2 1/2 miles. A running friend unaware of Annie's journey pulled up and jumped out of her car to join the swelling ranks of supporters, accompanying her in high heels. Whether in relays, alone on the street or on a life-affirming run, "That's what you love about it, the camaraderie," Annie says. "That's why you do it."

It was 11 hours since Annie had left the cemetery. She and a group of a dozen other runners climbed a gentle hill to witness, just over the crest, a crowd awaiting them outside her home.

Tanner Bell's wife Kristen screamed, "You did it!" as 40 well-wishers each presented a stunned Annie with a red rose. Brad took a homemade, hand-carved wooden medal from around his neck and placed it over his wife's head: "Annie Macdonald," it read, "40 miles, 40 years."