In 2008, the winds of Barack Obama’s campaign helped carry Utah’s usually beaten and kicked-down Dems to a historic win. For the first time in decades, the Democrats’ presidential candidate took Salt Lake County, staking a blue flag into the heart of one of the nation’s reddest states. Obama won by a margin of just 296 votes, but the Democratic tide was sufficient to elect a Democratic majority on the county council—the first time in over a decade—and re-elect Democratic Salt Lake County Mayor Peter Corroon.

But if the efficiency of the Obama machine won moderates and independents in Salt Lake County—as it did nationwide—by campaigning on “Change We Can Believe In,” the 2012 election stands ready to throw that change back in the faces of Democrats in local races, since Mitt-mania will be a driving force in getting the Republican vote this fall.

The popularity of Mitt Romney, Utah’s adopted son, famed for saving the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympic Winter Games, means nothing but trouble for Democrats, jeopardizing progressive races at every level of government. But, for Democrats, the biggest prize at stake is the Salt Lake County Mayor’s Office.

With Corroon stepping down, Utah Democrats are having their most competitive race in years with state Sens. Ross Romero and Ben McAdams, both representing Salt Lake City, vying to be mayor of Salt Lake County.

It’s a race of dueling styles and backgrounds. On progressive issues, the two may be photocopies of each other as far as voting records go, but stylistically, it’s a fire & ice matchup. Romero, a Catholic Latino, has connections that crisscross with power moneyhouse Zions Bank and local Latino communities. He was also a partner in one of the state’s oldest law firms and has eight years of experience doing the diplomatic work of a behind-the-scenes mover and shaker for Democrats on the Hill.

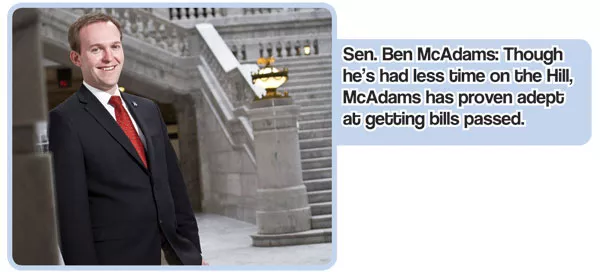

McAdams is a comparative rookie on the Hill, having just finished his third session, since he was appointed to fill the seat of retiring Sen. Scott McCoy in 2009 before being elected in 2010. In the past two sessions alone, however, the Mormon Democrat has passed 20 bills—nearly three times as many as Romero’s eight since Romero joined the Legislature in 2005. McAdams also made a name for himself when—as senior adviser to Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker—he helped push Salt Lake City’s landmark nondiscrimination ordinance, which protects lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender citizens in the city.

For both men, giving up a seat on the Hill to be the boss of the county represents the opportunity to enact policy without having to kiss any Republican rings. With both candidates’ experience working on statewide issues at the Legislature, they’re well-positioned to change the debate on state policy by pushing Utah’s most populous county to be the insurgent Democratic voice on major issues in a way that won’t be drowned out by the Republican Party’s megaphone in state government.

But some say that pitting the party’s brightest candidates against each other is a not-so-bright move that could weaken the party and weaken the winner’s chances in prevailing against the Republican candidate in the fall election.

Nevertheless, the immediate question facing the two blue contenders is: Which of these smart asses can pass the test?

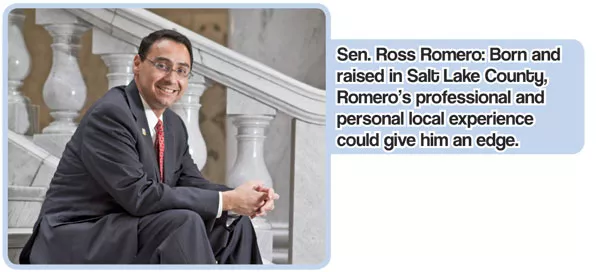

Sen. Ross Romero: “I am Salt Lake County.”

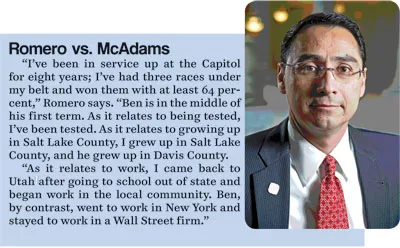

Sen. Ross Romero is the epitome of a professional. With chops that extend to community banking and employment law, and with nearly a decade of legislative experience, this is definitely not Romero’s first rodeo. But it may be his most important, as Romero is “all in,” by his own account. Thanks to the sometimes-cruel calculus of legislative redistricting, Romero will not have a seat in the 2013 Legislature and will be out of politics without a win in the county mayor’s race.

Which is exactly why Romero was not in the best seat at a recent University of Utah forum exploring questions of racism, white privilege and oppression. All of the panelists not running for major office were talking in grave tones about racism on campuses and communities across the country. Stuck in the middle was Romero, the one with the most to lose for being pegged by voters simply as a “diversity” candidate (exactly the label Romero avoided in an interview the day prior with City Weekly). But he’s also the one who, if elected, could do the most to help the county come to terms with its complex and ever-growing, ever-changing demographics.

A polished candidate, Romero is incredibly articulate, but also measured in his words. As other panelists began digressing on race in America, Romero was cautious with his answers, while his hands punctuated his rhetoric.

At one point, while speaking of unity, his fingers knit together and shook—meaning “collaboration” in the political sign language of the first President George Bush. He later briefly raised the purposeful thumbs-up of President Bill Clinton to punctuate a point. When a student in the crowd suggested that Utah is post-racial and discrimination might not be a factor in the workforce, Romero’s voice stayed steady but his arms crossed his chest.

“I don’t think we’re at that point yet,” Romero said, referencing the defeat of Senate Bill 51, which would have provided discrimination protections to LGBT Utahns.

“That bill failed,” Romero said. “So what is the inverse of that? That we are for discrimination in employment and housing for certain segments of the population? I am not for discrimination, so I have to repudiate that.”

But in that challenge also lie two dilemmas for Romero. As Senate Minority leader (meaning the leader of the minority party in the State Senate, e.g., the Democrats), Romero is also the first minority (in reference to his Latino heritage) in a leadership position in the Senate. Yet he doesn’t want to be defined by diversity.

His second dilemma is that as a leader in the Legislature, Romero puts himself front and center for his colleagues’ bills and takes the punches for them—even the nondiscrimination bill, sponsored by Romero’s mayoral challenger McAdams. Taking a bruising for his colleagues’ legislation, Romero says, is what leads to his own bills often being sacrificed at the conservative altar.

In the 2012 session, every bill Romero proposed was voted down or died in committee. The death of some were understandable, such as the bill to open up Republican caucus meetings to the general public—that bill never made it to a committee hearing. But others were more frustrating, such as a bill he pushed to let restaurants sample wine before they purchase it for their business. The bill didn’t allow for the swallowing of the wine, but nevertheless drew complaints it would encourage consumption. Still, the House spit the bill back rather than vote to pass it into law. It was the same for his bill to restrict teens from operating cell phones while driving and another to require new legislators to sit through a brief session on diversity and sensitivity training.

During a committee hearing on the sensitivity bill, one Republican, Sen. Casey Anderson, R-Cedar City, a freshman senator, had to have the concept of “gender identity” explained to him—that transgender individuals may self-identify with a gender different from the physical anatomy they were born with. The teachable moment was enough for Anderson to vote in favor of the bill, but none of his Republican colleagues did (they also didn’t ask any questions before voting Romero’s bill down).

Despite his businesslike approach, Romero does crack a sly grin at the suggestion that his bill may have taught one conservative on the Hill something about diversity.

“I don’t look at myself as running on diversity—but I will say this: Our nation is changing,” Romero says. “The demographics of our nation are changing, the demographics of our state and particularly of our county are changing. So, do I represent Salt Lake County? Absolutely.” He pauses. “Do I represent the state of Utah? Probably not quite yet. ...”

When Romero says that he is “Salt Lake County,” his roots in the community can back it up. He currently works at Zions Bank doing community banking for cities, towns and other local entities. Before that, he was a partner in Salt Lake City legal firm Jones Waldo from 2003 to 2007. He’s also sat on numerous boards, including the Utah Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, and was president of the Utah Minority Bar Association. But Romero says before his career success, his upbringing was much humbler.

“I grew up as a product of a public-schoolteacher mother and a stepdad that worked out at ATK in Magna,” Romero says. “I understand what it means to work every day and live paycheck to paycheck.” As the child of divorced parents, Romero found his time split between West Valley City and attending school on the east side where his mother taught. With a foot in both worlds, Romero grew up understanding both sides of the county, culturally and politically.

Now, though Romero doesn’t speak Spanish and lives on the east side in a district that’s more than 90 percent Caucasian, he and his wife send their two children to a school on the west side to learn Spanish.

Romero also says that as a Catholic Latino, “I’ve had many opportunities to be converted into this community’s major religion, but I always had a strong sense of who I was.” As the state’s first minority leader in the Legislature, Romero says that when representing Utah to other legislatures and other states, he’s a passionate cheerleader for Utah.

Inside the state, Romero says, he knows how to get things done—stressing diplomacy over flashy statements. While his bill performance may be lacking, Romero claims with pride his defense of Democrats on the Hill. Romero says he was first to call out former Sen. Chris Buttars, R-West Jordan, for his racially charged “black baby” comments on the Hill in 2008. He also had to orchestrate some budgetary wizardry to find the funds to help KUER do its We Shall Remain documentary series on American Indians in Utah, during a session when the economy was still in the dumps.

That being said, Romero admits that for a Democrat, he’s a fiscal conservative, and if elected as county mayor, he wouldn’t be asking voters to bond grandiose projects like a county convention center until core needs are addressed. He’s also not likely to bend over backward to attract new, large, out-of-state businesses when more resources could go to growing small local businesses already in the county, a business community he’s already made the rounds with multiple times in his current job as a community banker.

At the helm of the county, Romero could also broker wider conversations about policy, much like he and former House Leader Rep. David Litvack, D-Salt Lake City, did by hosting a public forum on alcohol policy in Utah and giving a platform to bar and restaurant owners and average Utahns, rather than just the Republican leadership voices in the Legislature.

Sen. Ben McAdams: From Earth Stains to Turning the Dial Against Discrimination

McAdams has a well-rehearsed, but sincere, sales pitch he delivers to delegates. City Weekly shadowed his tour of delegates in the Avenues as McAdams, assisted by staff, cruised through the heavily Democratic neighborhoods trying to meet and greet 30 delegates a night. The “greet” part always comes with congratulations to delegates for being nominated and letting them know he’s accessible and available any time they have questions.

This commitment to transparency is one put to the test when a City Weekly reporter asks McAdams’ about the band in which he played the electric guitar in high school. McAdams could not remember the band’s name, so he immediately called up a former bandmate—also a delegate—and put him on speakerphone. He confirms the group never had an official name … while McAdams congratulates him on becoming a delegate.

“I don’t know if we had [a name],” the staticky voice says before coming back with, “Was it Earth Stains?”

An homage to McAdams’ early days as an environmental advocate, perhaps? McAdams was the president of an environmental club in his high school before attending the University of Utah, where he took over as president of the College Democrats, succeeding his peer Charlie Luke, who now serves as Salt Lake City’s’ newest councilman.

For McAdams, it’s hard to trace when it was that the political bug really bit. He dabbled in politics in high school and college, but it wasn’t until his mission in Brazil, he says, where he saw how education inequality seemed to hold back entire swathes of the country’s citizens, and how he recognized the impact of bad policy on a people and the necessary potential of good public policies (For more on McAdams’ faith and politics, see “Choose the Radical,” City Weekly, Sept. 28, 2011).

“It’s just something that gets into your blood,” McAdams says of his political zeal.

A sure sign that politics is in your blood is a willingness to sell your blood—or at least your plasma—to supplement the poor pay that comes with working Democratic campaigns.

McAdams was a regular plasma donor during the waning days of the 1998 Scott Leckman for U.S. Senate campaign. Even after he had parlayed an internship with the Clinton White House into a temporary gig traveling to foreign nations to help prep for the Clintons before they landed in a country, McAdams found himself forced to live off plasma money.

“I would always pack in my bag a loaf of bread and peanut butter and jelly because I couldn’t afford to eat out,” McAdams says with a laugh.

Now, after having worked in New York City and Utah in securities and corporate law, and having rounded out his third successful legislative session with his name attached to the lion’s share of bills passed by his party, McAdams does eat a little bit better, but is still hungry—now for an executive seat.

Following McAdams on the campaign trail, it’s safe to say that for many in Salt Lake City’s Avenues, their only qualm with McAdams’ campaign is the idea of losing him as their senator. In one home, gay couple who’d been together for 18 years had nothing but praise for McAdams and simply told him to have his staff “back off” from calling them. In another, the delegate stopped to show his photo in a Salt Lake Tribune front-page article he framed about the Democratic caucus turnouts. In another home that had the relaxed feel of student housing, a delegate took pains to note to a reporter that McAdams is “my favorite politician in Utah right now.”

In another house, however, a delegate sat quietly as an antique clock ticked loudly over McAdams’ shoulder. She challenged him for supporting a bill passed in the 2012 session by Sen. Curtis Bramble, R-Provo. The bonding-act bill allows Salt Lake City, for example, to keep an environmental group from invalidating a bond measure for the Jordan Soccer Complex simply by stalling it in the courts.

It’s a technical argument that leaves the über-polite McAdams softly arguing that activist groups shouldn’t be able to run out the clock to defeat a voter-authorized bond.

“The change is that, since it’s being litigated, the clock stops so the benefit goes to the government,” the woman says. “The benefit is always to government—they have the money.”

McAdams disagreed. As an employee of Salt Lake City government, McAdams draws a lot of his community experience from working under the wings of Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker, and by default, he gets flak over Becker policies, as well—including the sports complex that environmental activists says will wreak havoc with the Jordan River ecosystem.

Being the Becker prodigy could also spell trouble in the county for McAdams in conservative circles—but it’s also an opportunity for him to work across the aisles.

In the 2012 session, McAdams helped draft a compromise to a Republican bill designed specifically to undo Becker’s recently passed anti-idling ordinance. McAdams negotiated to temper the Republican bill by allowing cities to continue, for example, to enforce anti-idling ordinances on vehicles so long as the idling car wasn’t on certain private properties, like a resident’s driveway or the drive-thru of a fast-food restaurant.

Perhaps McAdams greatest work of compromise was on the LGBT nondiscrimination ordinances that Salt Lake City first proposed in 2008. At that time, Sen. Buttars came out publicly to say he would overturn the ordinances in the Legislature. McAdams, then still just an adviser for Becker, told the mayor the ordinances were too important to have overturned.

“So, over the next six months, we had meetings with Sen. Buttars at his home and meetings with [conservative activist] Gayle Ruzicka. We met with the LGBT community, and when Salt Lake City adopted the ordinances in 2009, Sen. Buttars supported them, the LDS Church supported them and the LGBT community had a historic win,” McAdams says. “Today, 14 communities have adopted the protections, and 70 percent of Utahns support them.”

From that effort, McAdams took away more than just the warm fuzzies of having impact at the local level—he also learned that a coalition of communities is shaping the debate on the state level. While nondiscrimination protections still struggle to gain a foothold at the Legislature, the cause has garnered greater support than many could have imagined when they were first proposed in the 2008 session—and a lot of that momentum was built from communities in the county.

Back in the skeptical delegate’s house, McAdams responded to the delegate asking him what jurisdiction the county mayor’s office has on issues McAdams wants to build coalitions around.

“I think I’ve been effective on certain [legislative] issues,” McAdams says. “But the real big issues I care about—air quality, education—I don’t even feel like I even have a seat at the table up there.” While education is not exactly the jurisdiction of the county mayor, McAdams points out that people said the same thing about the nondiscrimination issue as well.

“I think there is a role for a regional leader to do that,” McAdams says.

(D)isastrous Matchup?

With the state’s top Democrats in the Legislature squaring off in the same race, more than one pundit has wondered aloud: Why put your two best performers in the same donkey show?

If the race goes beyond the county convention on April 14, it will be headed to a primary in June. In the interim, the campaign will heat up and the two contenders will have to start pitching themselves to a broader audience—and potentially have to start fighting a little rougher.

Salt Lake County Mayor Peter Corroon, however, says that the nature of campaigns means that a good race will produce better candidates in the long run.

“Yes, you spend some additional money and, yes, there may be some negatives brought out by one side or another,” Corroon says. “But by the end of the day, you get a better candidate with someone who has been battle-tested.”

Battle-tested is good, but battle-wounded is not, at least according to Matthew Burbank, a professor of political science at the University of Utah, who says such intra-party battles can have plenty of downsides.

“Given these two candidates, I would doubt that it would get terribly negative,” Burbank says. “But on the other hand, one of the things that clearly happens when you have a contested primary is the other side watches to see what happens. Some of that may come back to haunt you in the general election.”

So while there may not be much dirt-slinging by the two Dems, it could be the case that campaign rhetoric seeking to roust out the liberal vote could be used in the fall elections to scare away moderate Republicans and independents—the much-needed swing vote for a Democrat to take the county mayor’s seat.

Burbank says that doing well at the convention means keeping “liberal activists” happy, and activists and the swing votes are not likely on the same page.

“They’re not wildly liberal by the standards of many places, but at least by Utah standards, the Democrats of Salt Lake County are probably as liberal as it gets,” Burbank says.

Follow @EricSPeterson on Twitter for updates from the April 14 county convention, where delegates will vote for their candidates for county mayor and other offices.

| SkiLink Case Study When it comes to legislative voting records, McAdams and Romero have rarely disagreed. When it comes to county issues, they agree more often than not. But what may be most illustrative of the two candidates is the debate over SkiLink. The federal proposal would link Solitude and Canyons ski resorts with a gondola to create more than 6,000 combined acres of skiable terrain. When asked about the proposal as it was introduced in Congress, McAdams said he was against it because it thwarted local control and could hurt Salt Lake County’s watershed. Romero studied the issue for a time before also publicly coming out against it. “I think he studied it until a couple weeks ago when he decided he was against it,” McAdams says. “But the disappointment to me and many others is that while he was studying it, he was also fundraising off of it.” Indeed, during the time Romero had stated he was studying the issue, the Talisker Company, which owns Canyons Resort, held a fundraiser ball for Romero’s mayoral campaign. Romero doesn’t shy away from being an advocate for the tourism industry and says he did not want to reactively shut down the idea. Instead, he says, a compromise idea needs to be brokered. Romero says he would study paving over Guardsman Pass between the resorts and allowing only natural-gas- fueled buses to shuttle skiers between the resorts. “It would accomplish what I think a lot of people want on both sides—being very sensitive to the environment, yet touting this connectivity that would enhance the ski experience,” Romero says. |