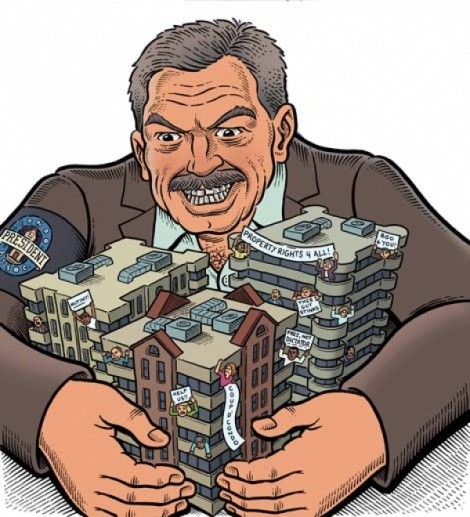

- Mario Zucca

Residents were restless at the January 2009 Towne Park Homeowners Association board meeting. Like guerrilla insurgents, the condo owners hoped to stage a coup against the HOA board “dictatorship.”

According to homeowners, the group’s mistrust grew out of the board’s botched attempt to repair the roof of Building 1, located at 300 East and 600 South in downtown Salt Lake City. When contractors declared bankruptcy in the middle of the job, condo owners found they had shelled out hundreds of thousands of dollars for an unfinished roof, which led to major water damage across multiple floors of the building.

At the January 2009 meeting, the board proposed another assessment for other repairs to skeptical owners who were already incensed after discovering that one of their board members had spent nearly a month in 2008 at a downtown hotel while condo renovations were underway, with condo owners footing the $4,867 hotel bill, according to homeowners who spoke to City Weekly.

When the vote failed to muster a majority of owners willing to foot the bill for building repairs, the board took the proposal back, amended it, and presented the proposal to the condo owners again in February 2009—this time, the assessment was approved. Or, at least that’s what owners were told, until one owner requested to see the vote tally and found the numbers didn’t add up. According to owners including Dylan Zwick, who now sits on the board for Towne Park, owners continued to demand to see the ballots until May 2010, when the board president told the owners they could not see the ballots and that she had stored them with her own personal lawyer.

Embattled by angry owners, the president eventually relented and produced the ballots, revealing a tally that fell far short of the numbers necessary to enact the assessment, Zwick says. Amid the furor over the recount, the president resigned and a number of the outspoken critics like Zwick took on board positions.

Regime change may have been needed at the Towne Park, but new board members say it wasn’t easy, considering that HOA boards operate in a shadowy area of state property laws where little accountability is required of them while being accorded nearly no legal liability and a lot of power over fellow homeowners.

“This combination is a perfect recipe for—if not outright corruption—then abuse,” says Zwick, a 30-year-old University of Utah mathematics student and new board member of the Towne Park Homeowners Association. “They’re kind of like these private little governments.”

Zwick and others faced intimidation from board members who had the power to behave either like benevolent monarchs or dictators.

However, an ombudsman’s office would mean spending more on more government—a concept few legislators on the Hill are fans of—and there’s also the challenge that many Utah lawmakers are landlords themselves or are involved with property-management companies. In fact, Utah Senate President Michael Waddoups, a more-than-well-known face in local HOA communities, operates Cooperative Property Management, a company that, according to its Website, works with many “notable properties,” including “Foxboro, Country Springs Centerville, Stansbury Condos, Vine Street Mod, and Homestead Farms,” offering a slate of accounting and maintenance services. Waddoups’ company was even contracted to Towne Park’s HOA during its recent upheaval.

Because of Waddoups’ property-management background and his elevated position of trust in the community, it is easy for condo owners to believe their HOA is in good hands when he’s involved. Often that’s the case—but not always, as Arlington Place HOA board members (which, in 2006-07, included City Weekly editor Jerre Wroble) learned the hard way. There, the HOA board—which contracted with Waddoups’ company to provide accounting assistance in 2004—discovered only too late it had long been employing an unlicensed and uninsured maintenance man whose criminal past included allegations of stalking and two separate charges of lewdness—nearly all of which was unknown until he left the employ of the HOA.

God of the Gaps

Before Zwick became the vice president of the Towne Park HOA, he, like many newcomers to the Condo Republic, had no idea what the CC&Rs, or the Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions agreement was, when he signed it. Zwick realizes now how important the agreement is, especially for what it leaves out.

“They’re essentially the governing documents of the condominium. They’re fairly long, but there are still a lot of possible situations left out,” Zwick says, adding that boards end up with a lot of power in interpreting all the things the documents don’t spell out explicitly. “The HOA board becomes a god of the gaps—anything not specifically addressed within the CC&Rs is almost completely up to the discretion of the board.”

Hand that leeway to a volunteer board, tasked with a lot of responsibility, a big bank account, and little or no compensation, and Zwick says you have a situation where boards can abuse their power, often out of sheer vindictiveness.

Zwick says he was once blissfully ignorant of condo politics until his dad, then retired and also a Towne Home condo owner, started telling him about bruising and nasty exchanges at meetings he had attended between frustrated condo owners and an intractable board. Zwick’s father started a Website challenging the board’s actions—including the board member’s hotel bill and the voting tallies on the assessments.

“My dad was retired, bored and I think he was just looking for a battle,” Zwick says with a laugh. Besides the Website, his dad posted flyers around the condo to advertise board actions. Ultimately, this insurrection succeeded, the board president resigned and several new members took positions on the board, including the younger Zwick.

“I have been on both sides of this,” Zwick says. “Some homeowners like to complain about everything and that can be annoying, but it’s what you sign on to.” In Zwick’s experience, a major challenge to fair HOA-board governance is the issue of power. Not only does being a “god of the gap” mean boards have a lot of discretion in interpreting condo rules, but they also have the added ability to punish condo owners with arbitrary fines, or, as he experienced firsthand, face legal intimidation from HOA-board lawyers.

If condo owners attempt to legally challenge their boards, the board’s legal fees are usually provided by the condo-owner fees, which means condo owners challenging their boards pay both for their own lawyers as well as their opposition’s legal fees. This situation gives boards more power to make legal threats, as Zwick’s father experienced when he was issued a cease-and-desist order from their board’s attorney. Zwick says the notice was “all bark and no bite,” since it demanded they stop the Website, threatening serious legal consequences if the Website reported anything libelous or untrue.

Ultimately, Zwick is supportive of a recently formed group, the Condo Owners Coalition of Utah, which is pushing for legislative backing to reforms for condo associations statewide. Zwick advocates for clear protections for condo owners’ access to voting and financial records, as well as articulating when boards can close meetings off from condo owners.

“If all you want to do is live in your condo, pay your dues and be left alone, you should be able to do that—but the problem is what happens if you start running into an issue,” Zwick says. “Then you start realizing how small your power is relative to the board’s.”