In his faded bluejeans, with specks of hay on his shirt and cow dung on his battered brown boots, Mike Noel swings a leg over his ATV and rattles off facts about the cattle market, his hay-growing operation and the drought.

A few low clouds are strung out in the fat, blue sky in Johnson Canyon on the outskirts of Kanab, where Noel, a 13-year Republican state representative, rules the roost on his 700-acre ranch. Here, Noel seems about as close to heaven as any Earth-bound creature.

But there is a static to Noel's joy, and all it takes is a glance to the east for him to view the cause: the 1.7 million-acre Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, a vast chunk of sandstone and desert that Noel believes is being mismanaged by federal land managers.

Noel can rattle off dozens of rules and regulations imposed by federal bureaucrats that he finds ridiculous.

And on this Tuesday morning in April, an hour after parsing out a 1,500-pound bale of hay to his 150-head cattle herd, Noel can think of two rules in particular he doesn't like—and they have to do with fire and poop.

"On this ground out here, when you build a fire, you're supposed to take a tin pan and you're supposed to build your fire in this tin pan," he says. "That doesn't even make sense to have to pack a tin pan."

And when venturing into Paria Canyon, where hikers must now obtain permits from the Bureau of Land Management before stepping onto the sand, Noel moves between laughter and disgust as he explains that hikers have to pack out their waste.

"If you hike down the Paria Canyon, you got to pack your own poop out. I mean, who wants to hike and go pack your own poop out in a bag?" he asks. "That turns the whole thing off for me that you gotta' go down there and pack your poo out. That's ridiculous."

Noel asks me what I think. I tell him that, with so many people and so little room to bury poop at a campsite, I see the logic in the practice.

Noel says he understands. He even sees the sense in it. Then, he says, "It's just not something I'm willing to do."

Mike Noel, the politician, has developed a reputation for his blustery style during the Legislature's annual 45-day session. There's too little time on the hill, he says, not to talk straight—not to tell people how he feels. His directness is often characterized as bluntness. And his bluntness is often interpreted as bullying.

Noel, though, doesn't consider himself a bully. But when cornered or attacked, Noel admits that he has a tendency to fight back. For many of his constituents in Kane, Garfield, San Juan, Beaver, Paiute, Sevier and Wayne counties—a sprawling area as big as some Eastern states, and home to a broad swath of Utah's red-rock country—Noel is the perfect representative. He is an uncompromising cheerleader for his country, Noel's country.

Attempts by preservationists to set aside land as wilderness, which could threaten grazing, mining and logging industries—all of which presently provide (or formerly provided) good-paying jobs for his constituents—are dismissed, often with noticeable disdain, by Noel. And his colleagues on the House Natural Resources, Agriculture & Environment Committee often follow his lead.

But Noel, the rancher, the lover of wide-open spaces, solitude, sparsely populated places and his ranch tucked between red-rock mesas, hugging the western border of the Grand Staircase, has more in common with the average desert-rat tree-hugger than some might think.

From the white chair in his living room, into which he slouches down while munching beef jerky made from his own cows and sipping on lemonade, Noel can see, through the tall plate windows, the edge of the Grand Staircase, the object of his love and hate, and the crown jewel of his political career.

A few miles from his home, after checking on his cattle grazing on a patch of land owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Noel tells me to shift the yellow ATV he let me borrow into low gear and activate the four-wheel drive. I follow him up a steep, sandy pitch, over sandstone boulders peeking out of the Earth. "It'll flip over on you if you're not careful," he warns.

We motor through a juniper-and-sagebrush forest and stop on a ledge. To the east, hundreds of feet below, is Noel's ranch. Behind it is the Grand Staircase, its white sandstone cliffs rising above an inky red mesa. Spreading out to the south is the Kaibab Plateau, rising up and up into pine forests before dropping off into the unseen depths of the Grand Canyon. And, to the north appears a staggering uplift of varying colors and open land, terminating in a set of shining red cliffs—a distant edge of Bryce Canyon.

"That's why they call it the Grand Staircase," Noel says, noting how the different sandstone formations gradually change and step up. "It's just an amazing place."

A Bull, Not a Bully

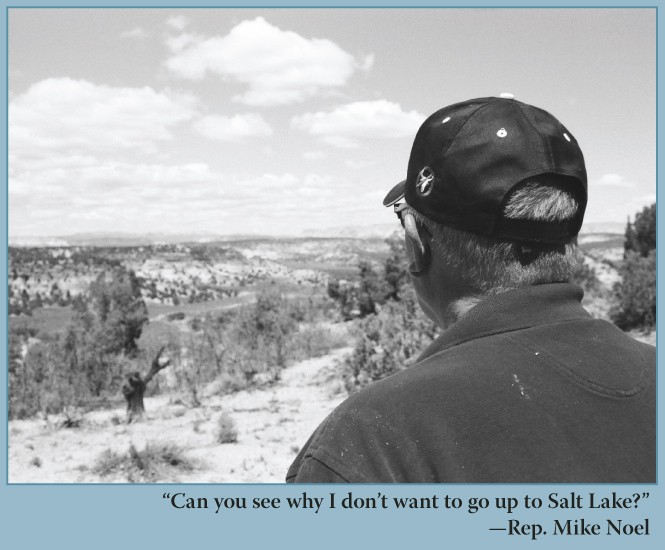

Noel marvels at the landscape around his ranch, saying he doesn't like going to Salt Lake City. For one, there are a lot of people there, and for another, the air is a lot filthier in the city during the winter than it is in Kanab.

Near a pond at Noel's ranch, Canada geese glide inches above the water. He straddles his ATV, rattling off the species of various waterfowl while recalling the decade that he ran the area bird count for the National Audubon Society. "What do you think about all this?" Noel asks. "Can you see why I don't want to go up to Salt Lake? I come back here and it's all smogged in, there in Salt Lake."

A couple of years ago, Noel says, he sat at this very site during a break from the session. He saw wild turkeys by the water, a bald eagle perched in a tree and a herd of deer on the hillside. "I said, 'What the heck am I doing up in Salt Lake City, man? I could be back down here.'"

But it would be disingenuous to say that Noel doesn't like being a legislator. Now in his 13th year representing Utah's District 73, Noel seems to revel in being the "herd bull of the House," a nickname that he says was handed down by his legislative colleagues.

Over the years, Noel has been a tireless champion for his district—or, at least, for the vision he has for his district. In step with his rural priorities that hinge on creating good jobs in mining, drilling, logging and ranching, he has become a capable foe of environmental groups looking to preserve swathes of the state as wilderness—hemming in natural resources that could be sucked from the ground.

Like many of his fellow lawmakers, Noel could sit silently behind the dais of the House Natural Resources, Agriculture & Environment Committee, hear out the concerns from environmental groups and citizens over the Wasatch Front's polluted air or opposition over oil and gas drilling in beloved, wild areas, but Noel speaks his mind.

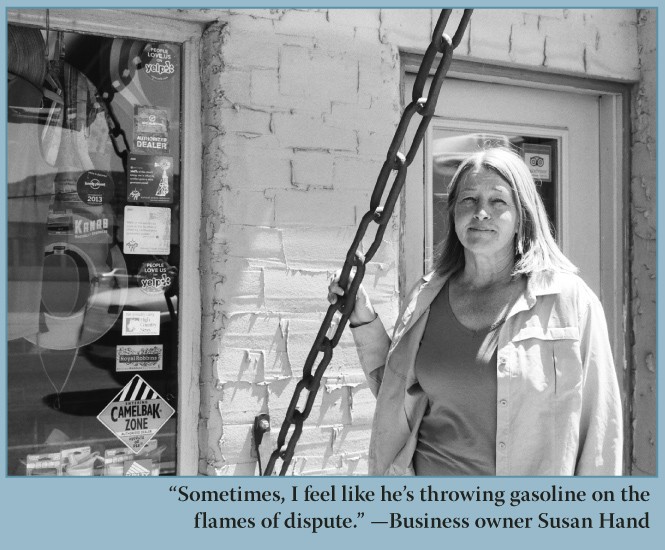

And, on a fairly routine basis, Noel's words offend. His legislative touch is about as gentle as a jackhammer, a personality quirk that he says his children and wife would agree with.

In 2013, while testifying in support of an air-quality bill, Joro Walker, an attorney and director of Western Resource Advocates' Utah office, caught the ire of Noel, who at the time was chairman of the committee.

Noel asked Walker if she'd ever sued the state—specifically, if she were involved in lawsuits aimed at the Alton Coal project in Kane County. Walker said she wasn't involved with that lawsuit—a comment that, to this day, Noel maintains was dishonest. Walker denies this, saying she was forthcoming with Noel's questions and told the truth.

At one point in the hearing, someone asked if Noel's questions are pertinent to the bill being discussed. He says that it's pertinent to him because, "I just want to know why she hates my grandkids and kids down there so they can't get any jobs down there."

David Garbett, staff attorney at the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, says there's no reason to mince words when it comes to Mike Noel. He's a "bully," Garbett says.

"He's flamboyant, he's extreme in his positions," Garbett says. "I think he makes this debate very personal, unfortunately, rather than having our decisions be about what's the best policy decision. For him, it's like, 'Why are you trying to harm my children, what are you trying to do to my grandchildren? My grandchildren need to be able to drive wherever they want on an ATV,' apparently. And I just think that's unfortunate that that's the sort of dialogue, or the place, that he always wants to take these discussions."

Noel doesn't like to hear that he's a bully. "I don't think I'm a bully," he says. Then he recounts all of the instances over the years where his words might have been construed as being bully-like.

He remembers an episode years ago when he told a young woman working for the Utah Rivers Council that her bill wouldn't get his vote. Why? "Because you guys have been suing the state of Utah," Noel recalls telling the woman. "If you want to really get along with people, you don't sue the state and do this and that."

"Anyway, she started crying," Noel says. "I say, 'Man, don't take it so seriously.' I wasn't trying to be mean. I just told her, 'your bill's not going through.' She'd worked the whole session to get that bill passed, and I killed the bill. So anyway, I guess that's mean. I can be kind of a jerk sometimes, there's no question about it. Ask my wife—I can be a little bit obnoxious."

Noel said these things on a Monday, and by Tuesday afternoon, the thought of himself as a bully was still on his mind, and he wasn't near so apologetic for his blunt nature. He explained that there's a finite amount of time to debate issues on the hill, and that he doesn't like beating around the bush when bills arise that impact his district.

And if that means he's a bully, so be it. "Well, you know what, I guess when I'm getting bullied, then I actually push back a little bit. It's like I said, 'You spur me, I'll spur you back.'"

It would be easy to say, and perhaps many Utahns assume, that Noel is just some career politician who has made a pet project of the state's effort to wrangle millions of acres of public lands from the federal government. But Noel doesn't fit easily into this box.

In between his heated moments on the hill, Noel is one of the go-to sources for lawmakers on the public-lands issue. Not only does he preside over a district dominated by massive patches of wide-open land and ranches, he is a rancher himself.

"He's been one of the leaders on the public-lands issues, as far as I'm concerned," says Rep. Lee Perry, R-Perry, who, prior to the 2014 session, took the reins from Noel as chairman of the natural resources committee. "When it comes to natural-resources and public lands, he's probably got as much knowledge on those issues as anybody out there."

Noel has the education and experience to back this up. He received a bachelor's degree in zoology from the University of California, Berkeley, which was signed by Ronald Reagan (a detail Noel enjoys pointing out); a master's degree in biology from South Dakota University; and completed some Ph.D. work at Utah State University.

And, perhaps more important than classroom experience, Noel cut his public-land chops on the ground as a 22-year employee of the federal government's Bureau of Land Management (BLM), an agency that, over the years, has become Noel's, and many other legislators', favorite punching bag.

A Political Birth

When President Bill Clinton drew a fat circle around much of Kane and Garfield counties in 1996, designating the Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, the move created many ripple effects, one of which prompted a stalwart BLM official named Mike Noel to resign from his government job.

At the time, Noel and Clinton both had their sights trained on the same thing: The Andalex coal mine, which Clinton cited as a threat to the area's labyrinthine canyons and sandstone desert, making the area a prime candidate for protection. At the same time, Noel was the top BLM official in charge of hammering out an environmental-impact study on the mine.

According to the Utah Geological Survey, Andalex, a Dutch mining company, was sitting on 62.3 billion tons of coal when Clinton designated the monument.

"Shortly after that, I resigned because I didn't really like the way the management was going," Noel says.

But at one time, Noel loved his BLM job. And, importantly, Noel says he saw sense in the BLM's mission, as defined in the Federal Land Policy Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, which stipulates that the BLM manage land for "multiple use, sustained yield and environmental protection."

Noel's first job was to conduct range studies, a task for which he was given a BLM pick-up truck. So tickled was Noel that he wrote his parents a letter saying he "got the best dang job."

As his career with the BLM moved along, and Noel's job titles shuffled, he says he grew frustrated with how land was managed and how the environmental-review process for projects on federal lands dragged out.

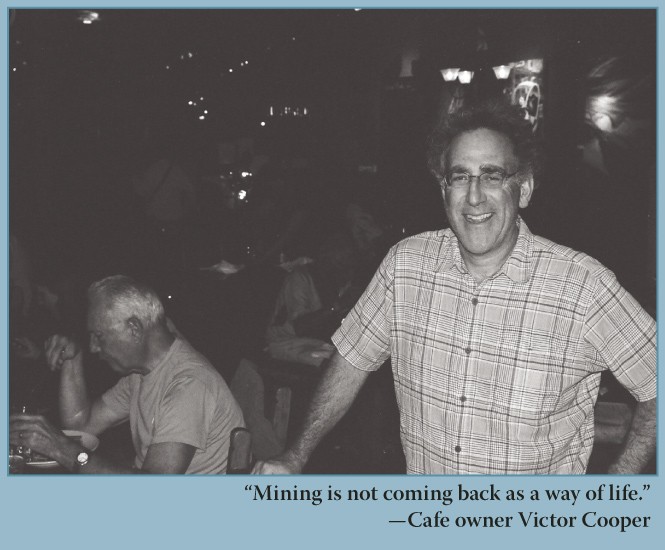

And each time Noel watched a person lose a job, saw a shuttered business on Main Street or heard about a person who was forced to leave town for work, he took it personally.

After leaving the BLM, Noel was offered a full-time job as the general manager of the Kane County Water Conservancy District—a job he holds to this day.

In 1995, Kaibab Industries shuttered its sawmill in nearby Fredonia, Ariz. A year later, it shut down its operations in Panguitch. At the time of the closures, the mills employed 275 people. Had the Andalex mine come to fruition, newspaper stories from 1996 say it would have provided 1,000 jobs.

"When [the Grand Staircase] went down and we lost that project, which we thought was going to be good for us, and it was done over that monument, that really got me fired up," Noel says. "I got pretty vocal."

Noel's political life didn't begin in earnest until the BLM moved to close what he says are "thousands of miles" of roads, known as RS 2477 roads, which create a spiderweb across the Grand Staircase. To oppose the road closures, Noel formed a group, People for the USA, to battle the BLM. When county leaders declined to step up and challenge the BLM, Noel says he filed a lawsuit. And, soon enough, the county leaders that had contemplated giving in to the BLM, were ousted and Noel was swept into the Legislature.

"It just turned out that there was enough people that wanted to fight for those roads," Noel says.

These roads, many of which snake through riverbeds, washes and trails, are the subject of ongoing litigation. Noel says he's confident the suit will be settled in the counties' favor. And if it does, these so-called roads will land squarely in the hands of counties to do with as they will, making it more difficult for land to be protected as wilderness.

"Every one of those roads, in general, all those roads go somewhere and do something," Noel says. "They allow you to get around. They don't create any problems. It's a vast wilderness out there, really."

Environmental groups, including the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, maintain that many of the roughly 36,000 miles of roads across the state that are being challenged are little more than renegade ATV trails. And the effort to seize them goes hand-in-hand with another bid, Senate Bill 143, or the Transfer of Public Lands Act, which was passed by the Legislature in 2012.

Although the bill's chief sponsor was Rep. Ken Ivory, R-West Jordan, Noel says the first draft of the bill would have allowed Utah, once it wrests around 30 million acres of federal land, to sell off large swaths. "I go, 'Well Ken, that's never been my idea and if that's the direction you're going, I won't be working with you on this,'" Noel says.

And herein lies the conflicting image of the Noel who says he loves wild land and the bona-fide political pro Noel, known to fan the flames of anti-federal government sentiment when it comes to public-lands management. And in the eyes of many, if the state of Utah manages to seize these federal lands, it's game-over for conservation.

But Noel just doesn't see it this way.

To Ivory, Noel recalls saying, "I'm not for selling these public lands. No. 1, all it's going to do is the highest bidder will be some wealthy guy that'll lock them all up, and no one will get to use them. ... I said I like the idea of what FLPMA tried to do, where it was multiple use and sustained yield. Where you took it, and you didn't destroy everything."

Noel says he plans to introduce legislation, the Public Lands Management Act, that would make it difficult for Utah, when and if the state is successful at taking over management, to sell off large swaths of public land. "There'll be pieces in it like FLPMA," he says.

Importantly, Noel says the state also shouldn't manage land the way it does school trust lands, which are treated like little more than a piggy bank.

"It is quite a bit different than SITLA [School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration]," Noel says. As he says this, Noel scans one of his alfalfa fields and the red-rock cliffs that hem in his ranch and embody the land that he says he loves so much.

"You're not going to sell these lands off," Noel says, training his eyes on his fields. "You'd have to cut my throat to sell off this ranch."