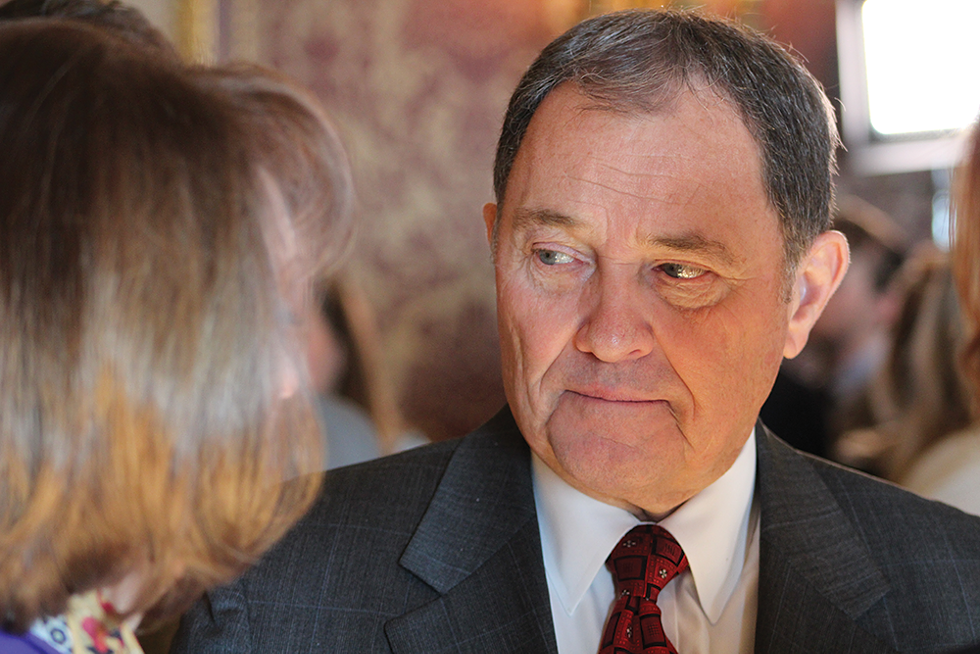

- Enrique Limón/FILE

On the night he signed HB 3001, the so-called medical cannabis "compromise" bill, into law, Gov. Gary Herbert released a statement praising opponents and proponents of the Proposition 2 ballot initiative for coming together and reaching an agreement that lawmakers could endorse. He commended those involved for ironing out crucial problems in the referendum and proclaimed that the Beehive State's new system would prevent the medicine from entering the black market. "With the passage of the Utah Medical Cannabis Act," Herbert said, "Utah now has the best-designed medical cannabis program in the country."

Does it? Critics say there's a lot of uncertainty about how that program will operate, given that the state is taking such an active role in distributing a substance illegal under federal law. Medical professionals, lawmakers and at least one member of the compromise coalition have concerns, questions and a wish list for what they hope to see changed in the upcoming legislative session. As Bonnie Kilgannon, a Davis County-based doctoral-prepared nurse-practitioner, says, "There's still a lot of work to be done."

Legislators gathered at the Capitol on Dec. 3 for a special session to pass the latest version of the controversial compromise, which includes provisions that limit which medical providers can recommend cannabis-based treatment and require state- and privately employed pharmacists to provide dosing directions to patients. The new law renders moot Prop 2, the ballot initiative voters approved last month. Kilgannon watched from the gallery during the House and Senate debates, anxious to see whether physician assistants and advanced-practice registered nurses like her would be allowed to recommend cannabis as a treatment option.

"When the first compromise came out before the election, they had pretty much gutted Proposition 2," Kilgannon says, days after the special session. She worked with House Speaker Greg Hughes to add advanced-practice registered nurses and physician assistants to the list of medical professionals who can recommend patients get a cannabis card. The system proposed in an earlier draft severely limited which providers could advise Utahns to try the new form of medicine. "Patient access was going to be severely limited," she says. By the time Herbert signed the bill into law, Kilgannon had gotten her wish.

She's crossing her fingers that lawmakers will still be open to tinkering with the bill come January, when they're back in session. "We're hoping they make further improvements, and we're hoping they don't do further damage."

Kilgannon wants to see nurse practitioners be eligible for appointment to the "compassionate use board," a panel that will evaluate on a case-by-case basis whether to recommend that certain patients, children and young adults receive a cannabis card. She'd also like the qualifying conditions list broadened to include mental illnesses like depression and anxiety. "Benzodiazepine abuse is every bit as much a concern to me as opiate abuse is," Kilgannon says about the anxiety-reducing sedative, "and medical cannabis has been shown to assist with anxiety disorders and insomnia."

Those who backed both Prop 2 and the compromise say the agreement preserves the core of the ballot initiative. But there are key differences—perhaps the most important of which is where patients can access the medication. Under Prop 2, they would've gone to a private pharmacy. Per the new law, the state will play a major distribution role by operating a central fill pharmacy responsible for distributing the drug to a local health department for patient pickup.

Cannabis card holders could also go to one of seven—or 10, if the central fill isn't up and running within a few years—privately owned dispensaries, each of which must employ at least one full-time pharmacist. "They're going to be kind of the dosing gatekeeper at the dispensary level," Connor Boyack, Libertas Institute founder and compromise negotiator, says.

Pharmacists are another point of contention. Ken Shifrar, an East Millcreek resident, has been a pharmacist since 1979. Although he's not currently practicing, he worries the new law will put his peers' licenses at risk. In his telling, pharmacists are licensed at the state level, but they depend on the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy for federal reciprocity so they can practice in other states. He's not sure how the feds are going to view pharmacists dispensing, monitoring and dosing a Schedule I drug, so he doesn't know what the future will hold for peers employed at private dispensaries or at the state's central fill. "This is the first state that's had the arrogance to do something like this," he says.

Shifrar also hasn't yet heard from the state's Department of Professional Licensing about how they'll deal with pharmacists working with the substance. The uncertainty makes him wonder who would choose to work with medical cannabis. "Not a single person I know is going to risk their license by becoming a cannabis dispensary," he says.

Jennifer Bolton, a spokesperson with the state, released a statement to City Weekly noting that, "The Utah Department of Commerce will not pursue disciplinary action for treatment of cannabis against license holders whose treatment with cannabis complies with the provisions of the Utah Medical Cannabis Act," and that they currently don't have any plans to issue further directives to license holders.

Libertas' Boyack says fears like Shifrar's are unfounded, noting that there are state criminal and civil protections written into the law, and participating pharmacists are not at risk of losing a DEA license, which allows medical professionals to prescribe controlled substances. "In the world of pharmacists, it is the pharmacy that has a federal license. The pharmacist has no such risk," Boyack says. "We're quite confident this is not going to be the poison pill some critics claim it is."

Boyack believes the reworked law is a step in the right direction, but, "it's certainly not a final destination, by any means." He expects to talk with lawmakers about increasing the number of private dispensaries, controlling cost so patients aren't forced to rely on the black market and expanding the qualifying conditions list. "Our intent is eventually to see the condition list completely done away with so that doctors and pharmacists working together can, at their discretion, use cannabis as a treatment option and not be handcuffed arbitrarily by a list the Legislature came up with," he says.

Sen. Luz Escamilla, D-Salt Lake City, already has submitted a new bill designed to eliminate some confusing wording and add two amendments that'd add protections for state employees and make appointees of the compassionate use board subject to Senate confirmation. "I think the current legislation is not feasible for implementation," Escamilla says. "I understand we're gonna make a lot of changes and a lot of bills are going to be taking place as we try to tackle a pretty complicated issue, but the way this bill is structured, I don't know it's going to work."

Despite his role in negotiating the compromise, Boyack knows the new law isn't perfect. He says he's not sure how the central fill is going to be implemented, or how the state is going to allow patients to use their debit card to purchase their medicine, given that federal banking laws prohibit banks from taking money from cannabis sales. "We don't think any of this is going to work. It's not like we share their vision or their hope," he says. "We think the central fill has many features that present a challenge to ever getting it up and running, or keeping it up and running."

Like many, Escamilla expects medical cannabis to become a perennial legislative issue, as lawmakers tinker with the program and strive to meet the governor's extravagant claim of Utah exceptionalism. "This is going to be an incremental process," she says, offering a prediction: "It's going to be pretty painful."