On Jan. 11, 2011, John Harja, then-director of Utah’s Public Lands Policy Coordination Office, calmly sat down in the budget hot seat in front of the Natural Resources Appropriations Committee. The committee had been grilling agency heads on budget cuts that might have to come out of their organizations to meet the required cuts affecting all of state government.

Harja wasn’t nervous, despite the fact that while legislative fiscal analysts were recommending minor cuts from other government programs, they specifically recommended Harja’s entire office be scrapped due to poor accounting of taxpayer resources and poor planning of the office’s goals.

Harja not only politely disagreed with the fiscal analyst, but also decided it was as good a time as any to ask for more money for his office.

“So, in fact, rather than say anything more about the proposed cuts, I’m going to ask you for even more funds,” Harja said. “I need more.”

That Harja sidestepped his office’s annihilation—and by the end of the session secured $400,000 in extra litigation funding, as well as $22,200 in unrestricted funds—speaks to how important the Utah Legislature and the Governor’s Office feel is the work of the Public Lands Policy Coordination Office (PLPCO).

The office’s mission is to coordinate all government voices in the state to stand up against the federal government and pry off the kung fu grip the Bureau of Land Management and the Department of the Interior has on the state’s public lands.

According to some estimates, 60 percent of Utah land is owned by the U.S. government. This doesn’t sit well with oil and gas developers, off-road-vehicle weekend warriors and many rural Utahns who chafe at not having control of the dirt underneath their feet.

PLPCO is litigating to reclaim approximately 18,784 rural roads across the state in a massive legal battle that, if successful, could also potentially undo the protected status of millions of acres of federally designated wilderness-study areas. The process of claiming back such roads requires attorneys and field agents to use an advanced digital-mapping system to track the roads and travel to rural areas of the state to interview witnesses and explore the disputed roads.

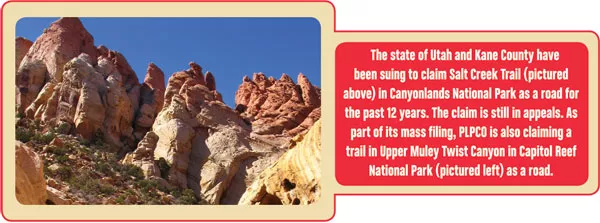

In 2005, the state filed a similar claim on seven roads in federal court. The judge has so far ruled on only two of the roads, located in Emery County. San Juan County has been in a legal battle over Salt Creek Trail, a single jeep road in Canyonlands National Park, for the past 12 years. The case is still in appeals. According to environmental advocacy group Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), the county has spent $1 million litigating just that road.

The herculean task of litigating 18,784 roads requires money and staff, which is why Harja informed the committee that his office needed more help. At the time of Harja’s January committee meeting, he had already taken on a new intern, who was something of a protégé of Harja’s, as indicated by documents City Weekly received through an open-records request. The intern, Christine Osborne, was taken on for an unusual “indefinite” internship. Roughly three months after starting her internship, she was given a full-time position starting at $63,000 a year.

Osborne’s most recent work experience prior to joining the office? Playing the bassoon in the Utah Symphony.

Harja acknowledges that the Governor’s Office did receive a complaint in early 2011 alleging an inappropriate relationship between Harja and Osborne.

“Those [allegations] were false and dealt with a long time ago,” Harja told City Weekly during a November 2011 interview, during which he reiterated that he had “no relationship” with Osborne.

According to the Governor’s Office, the state’s human-resources department investigated the allegations and “determined there was neither violation of policy, nor illegal conduct by PLPCO staff.”

While her role in the office was considered questionable even by PLPCO staff, perhaps most perplexing is how an office that has received millions in taxpayer funds to reclaim lands for the state—ostensibly to help bring in more tax revenue—was able to ignore the 2009 advice of legislative auditors, who suggested better oversight and accounting of the office’s finances.

Harja argued at the January 2011 committee meeting that the nature of dealing with so many different local and federal agencies made it so he couldn’t strictly follow auditors’ 2009 suggestions about creating measurements to track the office’s progress.

The office’s plan following the 2011 session, according to documents, appears to have been business as usual. But a shake-up did eventually occur at the office in December 2011. The week before the Governor’s Office turned over more than 500 pages of documents to City Weekly about the office, including e-mails about Harja and Osborne, Harja was replaced as director of PLPCO and accepted a position as an advisor at the Utah Department of Agriculture & Food.

Roads Less Traveled

In December 2011, Utah blazed new trails in public-lands litigation by being the first state to file notice of intent to sue to retake ownership of 18,784 roads in 22 rural counties. The state claims the right-of-way to these roads based on Revised Statute 2477, a law passed by Congress in 1866 to give settlers rights-of-way to the paths and trails they’d carved out of territorial lands (see p. 19).

The notices of intent served as the warning shot, giving the federal government 180 days to consider an alternative solution before the legal showdown really begins.

For Harja, the payoff for the years’ worth of preparation for litigation and preparation is simple.

“A transportation network that we can own,” Harja says.

SUWA attorney Heidi McIntosh disagrees.

“This really isn’t about roads,” McIntosh says. “It’s about trying to control federal public lands.” McIntosh points to the case of the Salt Creek Canyon feud, where San Juan County sued over the Salt Creek Trail in Canyonlands National Park to claim it as a road. The road was actually a streambed, and the county had previously been upset that SUWA had prevailed in court to prevent Jeeps from driving up the rugged path. “Jeeps would hit a rock, and all of the fluid and oil would drain into the creek,” destroy the vegetation and contaminate the stream, McIntosh says.

McIntosh highlights this case to point out that PLPCO’s claims on 18,784 roads—many of which are, in fact, dirt paths, streambeds and cowboy trails—stand to be an incredible taxpayer boondoggle. According to documents McIntosh received from the state in an open-records request, 113 of the 18,784 roads cross over national parks like Arches in Moab and Capitol Reef National Park near Torrey.

“It’s their attempt at shock and awe, because they can’t be serious about litigating 18,000 claims,” McIntosh says. She says San Juan County spent $1 million litigating the Salt Creek case alone, which they lost over a 12-day trial but are still appealing.

PLPCO attorneys got their first taste of what might happen to the majority of those 18,784 roads based on a Nov. 17, 2011, hearing before Utah District Court Judge Dee Benson.

The case had been filed in 2005 by the county and the state of Utah in a move to reclaim seven RS2477 roads in Emery County. Utah filed nearly 400 pages of exhibit documents as evidence of the county’s ownership of the roads.

During a hearing on the federal government’s motion for summary judgment—a move to decide a case before it goes to trial—Benson said that the motion and the evidence submitted in support of that motion needed to be streamlined.

“This case is the perfect example of the system that I find cumbersome and difficult. You have all … ‘flooded’ may be too much of an exaggeration, but you have provided the Court with a lot of facts,” Benson said of the filings.

Emery County had employed the same painstaking evidence procedures that PLPCO is preparing for its 18,784 road claims—using advanced digital-mapping systems, and sending attorneys and field agents to interview witnesses and explore the disputed roads. Benson wasn’t satisfied.

“What I need to find out is whether the county or the state or both received some communication by writing or orally that the right-of-way they think they have, they don’t,” Benson said.

The issue comes down to a legal standard known as “case or controversy,” which simply follows a no harm/no foul logic. In the case of the roads action, Benson argued that if you can’t prove the feds claimed your road, then you can’t sue to definitively make the road yours.

Benson told the state that even when the federal government designated a wilderness-study area that encompassed land where an old RS2477 road might exist, it would not count as the legal harm necessary to allow the state to sue to get it back. In order for the state to be able to even begin the process, the RS2477 road would likely have to be one the BLM explicitly closed. In the past decade, that would only include a handful of roads throughout Utah. After more than six years in litigation, Benson told attorneys for the state of Utah that this ruling shouldn’t come as a surprise. “I am not telling counsel anything that you don’t already know.”

In the Nov. 17 hearing, Benson partially ruled in favor of the United States, finding that one road could not be claimed by the county and that any claim to a second road was barred by a statute-of-limitations lapse. As for the rest of the roads, Benson needed more time and scheduled another evidentiary hearing on the motion for the end of January 2012.

No Matter the Cost

Harja inherited the PLPCO office in 2008 from predecessor Lynn Stevens, an outspoken San Juan County Commissioner who drew ire from legislators during his short tenure for not keeping track of office financials, which resulted in auditors noting that Stevens had the state expense his weekly car travel between Salt Lake City and his home in Blanding, roughly seven hours to the south. Stevens retired in 2007.

Even with state auditors highlighting Stevens’ travel expenses as a reason why the office needed to get a grip on its finances and keep track of progress, the office was flush with cash—more than they could spend, in fact. The 2009 Legislature allowed the office to keep $260,000 that had been given to the office in 2008. Unspent funds normally go back into the state’s coffers, but the office was able to successfully lobby to keep the money to spend on office equipment and software. Currently the office has $400,000 in reserve funds waiting to be spent on litigation expenses.

Since fiscal year 2010, the office has had roughly a $1.5 million annual budget. The state has also stockpiled $2 million in reserve funds since 2010 for “public lands litigation,” which has sat in a fund untouched. According to an official with the Governor’s Office, that money could be used by other agencies.

Harja’s supervisor, Michael Mower, the state planning coordinator and deputy chief of staff to the governor, says the state’s return on investing in PLPCO has been a major one, and not just in the recent massive RS2477 filing.

“PLPCO staff, including John Harja, have helped the state secure millions in additional tax dollars and mineral-lease payments through their work in helping to facilitate land exchanges,” Mower writes via e-mail. He says the office is also tasked with numerous other important functions involving interactions with the federal government, archaeological permitting and the roads battle. The December 2011 filing on the 18,784 roads “involved field crews, [Geographic Information System] experts, attorneys and other support staff to evaluate the evidence and get the documents prepared and sent.”

Harja decided at the beginning of 2011 that the office needed a new member of its team to aid in this project. In January 2011, he took on Christine Osborne as an indefinite intern.

“Our new special woman”

Osborne was offered a full-time position after only a little more than three months in the office—impressive since she was still juggling her symphony duties during her internship. In May 2011, Osborne was less than warmly welcomed into the PLPCO office as a full-time employee,

according to an e-mail sent from PLPCO Senior Policy Analyst Judy Edwards to Pam Blackham-Bailey, an office administrator with the Governor’s Office.

“Our new special woman employee is making more than Tiffany [Pezzulo], who happens to be a lawyer and has worked here for several years,” Edwards wrote. In a follow-up e-mail that day, Bailey responded, “Whatta mess.”

That Osborne started at $63,000, Harja argued later, was not unusual for his office, since he tries to pay well to attract competent staff. In an interview with City Weekly in November, Harja defended the hire, pointing out that Osborne also had studied public-lands issues in the past.

“She had a [Masters of Public Administration] from the University of Utah—or at least part of an MPA,” Harja said. Osborne did start an MPA program with a Natural Resources Concentration in 1993, but never completed it, according to her resume. (Osborne did not respond to requests for comment for this story.)

In an e-mailed statement, Mower says Osborne’s hiring was one that came after positive recommendations from a few PLPCO colleagues, and was one the governor was not involved in directly. Mower also says that while Osborne didn’t complete her degree in Natural Resources Management, she did carry a 4.0 and had some experience with environmental-impact statements and National Environmental Policy Act documents.

According to Osborne’s résumé, that experience came from her internship with the environmental planning company Bear West in the summer of 1995—16 years before her hire. But Osborne did have experience in public-lands issues prior to 1995, as she also served as a public-lands resource specialist for the Utah Sierra Club. Her environmental activism helped get her quoted in daily papers in the ’90s, criticizing land policies of the first Bush administration.

But the objections to Osborne’s hire from within the PLPCO office went beyond questioning her work experience.

Edwards arranged to have a meeting with Harja on Friday, March 5, 2011, at a time when the office was closed. According to a string of e-mails, Edwards came to meet with Harja, but changed her mind and left as soon as she got there.

When Harja e-mailed Edwards about why she had left so suddenly, Edwards wrote. “It’s Friday. No one else in the office, not your lawyers, advisors, paralegal, analysts or admin assistant, but your handpicked ‘biking buddy’ intern needs to be there???”

The following day, Edwards again challenged Harja in an e-mail about the friendship she perceived he had with the intern.

“I hope you understand yesterday when I said I could read the situation with Christine. Please know that she telegraphs better than a neon billboard. I would encourage you to back out of that (whatever it is and at whatever stage) ASAP,” Edwards wrote, adding “there is just no reason a new part-time intern needs to talk to the director in whispers in the outside hall. No need to defend it to me but I’m sure there are other instances that people are noticing and it just won’t end well. Just a word to the wise. Enough Said!”

That wasn’t the extent of the controversy surrounding Osborne’s role in the office. Her pro-environmental past came back to haunt her when, according to e-mails, an anonymous flier was sent to the Utah Association of Counties. For an association whose members generally share a room with environmental advocates only when that room is a courtroom, the news that Harja had hired Osborne caused the association’s board of directors to meet on Friday, June 24, 2011, and cast a unanimous vote of no confidence in Harja.

Osborne was soon officially let go. But Harja helped land Osborne a position at the Department of Environmental Quality to help the department with environmental-impact statements. On June 30, 2011, DEQ director Amanda Smith agreed to take Osborne on as a research consultant and replied to Harja in an e-mail that reviewing environmental-impact statements “is a role Christine can play—in close coordination with a division staff person.”

But while Osborne physically relocated to the DEQ office, the funds for her salary were still coming from the PLPCO office. And she was also still working for Harja, according to e-mails showing her continuing to work on PLPCO business unrelated to the RS2477 battle.

In September 2011, Harja decided that Osborne was ready for a promotion and e-mailed Smith on Sept. 6, 2011, to propose creating a joint position for Osborne between the two agencies.

“I understand someone is retiring from the section [Osborne] is in. I certainly don’t want to presume anything, but wonder if we could create a shared position for her with that money?” Harja wrote.

Harja, unable to get hold of Smith on the phone, e-mailed her again on Sept. 19 to see what she thought. “I think we could both benefit by having her as a joint employee,” Harja wrote. “Perhaps we could put together a hybrid sort of salary, mixing both agency needs … or?”

While documents City Weekly obtained from the Governor’s Office don’t show a response from Smith, an Oct. 12, 2011, e-mail from Osborne shows her accepting a new joint position between the offices. “I am committed to providing both DEQ and PLPCO with the highest quality work and a strong sense of collaboration, cooperation and service.”

Who’s the Boss?

Harja’s former boss Mower argues that, despite ignoring legislative auditors in 2009, the PLPCO office did complete its major goal of making sure legal notices were filed on time for the roads. The work of the office, he says, can’t necessarily be measured by standard performance metrics.

“Outcomes for the office are based on actions proposed by outside parties and ebb and flow with the nature and timing of those actions,” Mower writes. “These actions are tied to the substance of each individual action and are not suitable for widget-based metrics.”

But the goal of filing on 18,784 roads, Mower says, was an objective put to the office by legislative committees and the Constitutional Defense Council. The CDC, which provides the lion’s share of PLPCO’s funding, was created by the Legislature in 1994 and is comprised of the governor, members of the Legislature, county commissioners and different agency heads.

“The [filing] goal represented a huge task for the team, and the team was consistently reminded of the goal throughout 2011,” Mower writes.

But this goal was not clear to the PLPCO staff as a whole, according to a consultant’s report completed for the office in August 2011 that examined the office’s workings. Consultant Jill Carter reported that “there have been no performance-related goals and objectives written for employees.” Carter also reported PLPCO staff as saying that “John [Harja] expects people to be self starters but he doesn’t very often provide people with direction, as a result, not all staff appear to be busy and engaged in their work.”

Regardless of the dysfunction in the office, the Legislature may have spared the office from being mothballed in 2011 to ensure the office met the state’s deadline to sue the United States and not waste the work they had already done.

In 2000, the state had filed a preliminary document with the federal government about the rural roads. This set off a 12-year statute of limitations—the PLPCO office had to meet its 2011 filing deadline or face the possibility that the state might not be able to file at all.

The CDC created a fund in the early 2000s dedicated solely to fund the RS2477 roads battle and has had an even greater stake in making sure the office made its deadline. The CDC provides for roughly two-thirds of the office’s funding, according to Harja, and receives its money from royalties off of mineral leases from development in the state-trust lands.

The fact that the office receives most of its funding from development royalties is cause for concern from environmentalists, who question how the office can also independently weigh in on disputes on proposed developments, since developments fund the office.

Mower says the office still coordinates with other agencies and that PLPCO has brokered fair compromises on contentious issues in the past, such as a plan to protect 10,000-year-old cave art near Nine Mile Canyon while still allowing nearby natural-gas development.

Harja says the money from the CDC is for the RS2477 project and, therefore, there isn’t a conflict. “That money from development [royalties] is used to maintain our transportation network,” Harja says.

But members of the Legislature, as well as the CDC, are well aware of what those roads could do for development and control of the lands. At the January 2011 committee hearing where Harja sidestepped his office’s elimination, CDC member and appropriations-committee member Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, told the committee too much had been invested in the office to stop now. Noel referred to a conversation he once had with a SUWA member and other environmentalists who conceded that “if there is a road in a wilderness area, it’s not a wilderness area,” Noel said.

“We are going to put hundreds, if not thousands, of roads on the book for the state of Utah for our kids, and we don’t have to protect anything because they will be our roads,” Noel said. “To stop now would be huge mistake.”

While the PLPCO office under Harja has been pushing toward a fateful showdown with the federal government, it seems that after spending more than $8 million since 2008—not counting the $2.4 million in accessible reserve funds—the overwhelming majority of the 18,784 claims could be dismissed if Benson’s ruling in the Emery County case sets a precedent. The federal government hasn’t sought to close off or shut down most of the roads—probably because they never knew they existed.

The tug-of-war for land will continue under PLPCO’s new director, former national BLM director Kathleen Clarke, and the state will continue to fight for the right to develop lands and have better control over them as a means of adding more revenue to the state and flexing sovereignty in the face of brutish federal authorities.

With Clarke as the new head, though, taxpayers won’t know yet if she will be the first director in the office’s history to institute the performance and accountability measures suggested by legislative auditors. But what is certain is that bills will stack up—in 2011, the roads program was one of the few to get new funding.

“Why you would spend that kind of money when you’ve got 45 kids in a classroom defies good common sense,” McIntosh says. “But that’s how they decided to prioritize their resources.”