- Sarah Arnoff

- Police Chief Mike Brown

Admittedly, Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill doesn't have all the answers.

He can't answer, for instance, why three police officers weren't able to disarm and subdue a lone knife-wielding man without killing him. Or why a 50-year-old African-American would be stopped for a minor bicycle infraction in the first place. Gill can't comment on why police aim for a person's torso instead of their extremities. Or say for sure what, if any, training that police who fatally shoot a man are required to complete before they're allowed back on the street.

He doesn't have the answers because he's not a cop; it's not in his bailiwick, and the DA has no authority over police departments. But Gill encourages citizens to ask those questions nonetheless.

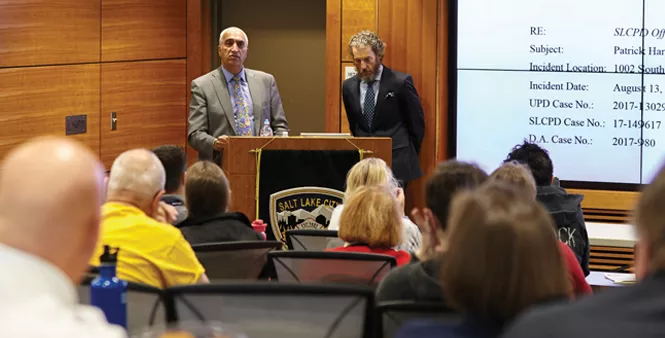

Inside the Salt Lake City Public Safety Building on a recent Wednesday evening, Gill analyzed the death of Patrick Harmon, the victim of a controversial Aug. 13 police shooting. He addressed a room of upset residents—at least a few of whom had within the week called for his job. For more than 90 minutes, Gill fielded questions posed by citizens in the Community Activist Group, which convenes twice a month to address policing in the city. (CAG also is said to stand for Community Advocates Group or Community Action Group.) In a balanced tone that neither downplayed the tragedy nor showed signs that his position had wavered, Gill responded to every question.

When the query touched on police policy or legislation, he listened in its entirety—many times agreeing with the question's premise—before reminding the crowd that he couldn't unilaterally change the law or police practices.

But he could answer, for one, why he ruled the shooting "justified"—a charged term but one Gill uses in its narrowest legal sense. To that end, he detailed the evidence that was presented to him and outlined legal parameters. Police can use lethal force if they are reasonably fearful for their safety or the safety of others, and Gill doubted he could prove otherwise if he took it to trial. He was there to answer why.

"It's very fundamentally important that you should be able to ask me these questions, whether it's me or anybody else that's an elected official," Gill said. "You should be able to say, 'I don't agree with you; prove to us what's going on,' and question me. It's my responsibility to try to answer for you the best that I can. We may have a disagreement, but I want you to understand where I'm coming from and the parameters I have to work with. But you get to ask."

The opportunity for citizens to directly confront top-ranking officials is rare, but it happens at CAG meetings. Salt Lake City's CAG was organized in the aftermath of a police shooting in February 2016. Abdi Mohamed, a 17-year-old Somali refugee, was severely injured near the downtown homeless shelter where he was shot by an officer.

By and large, even the most critical CAG members have lauded Police Chief Mike Brown for opening the doors to his department. And Brown believes the result is increased trust and transparency.

"It is hard to hate up close," he writes in an email. "When we sit and talk about the issues and have the difficult discussions, that is when we can make change and learn how to best serve."

The CAG meetings are at their most heated, however, after controversial police action. Brown admits the impulse by some to paint the entire force with a broad brush affects morale.

"To have all the good incidents often go unnoticed and be overshadowed is hard," Brown declares. "But our officers come to work every day and continue to serve, and it makes the compliments we receive all the more meaningful."

It's the controversial incidents—involving life-or-death decisions—that carry the most weight, and some activists question whether the 2-year-old CAG is doing enough.

- Enrique Limon

- Lex Scott

Grassroots

Activists and family members of police-shooting victims had been agitating for change prior to the Mohamed shooting. Heidi Keilbaugh recalls the exact time and day her partner, James Barker, was fatally shot by police in the Avenues neighborhood: Jan. 8, 2015, at 3:30 p.m., a moment that still haunts her. Resolutely, she believes the confrontation could have been resolved without lethal force, although police and the DA ruled it justified. In the aftermath, she says, hundreds of people rallied—familiar faces as well as strangers.

By then, excessive police force had become a national conversation. Locally, pressure mounted and the city agreed to host a town hall meeting. Deeda Seed, a former city councilwoman and longtime activist, was there. What transpired was positive messaging but little change, she says. "It happened—but there was no action as a result."

Keilbaugh became a founding member of a Facebook group called Utahns for Peaceful Resolution. Around the same time, an informal band of citizens—with representatives from Utah Against Police Brutality, United Front Party, Utah Copwatch, the American Civil Liberties Union and others—coalesced. They called the group Community Coalition for Police Reform, which began meeting and discussing overarching community problems.

In 2015, as two mayoral candidates squared off—incumbent Ralph Becker and Jackie Biskupski, then with the Salt Lake County Sheriff's Office—the activist community drafted a survey on police reform and asked the candidates to fill it out.

Seed says they were impressed by Biskupski's answers. In November of that year, voters sent Biskupski to city hall, and the Community Coalition for Police Reform saw the change as an opportunity.

"We said you had concerns; we have concerns," Seed recalls. "We would love nothing more than to see if there are policy solutions and to talk and make good change for our community."

Biskupski assumed office around the one-year anniversary of Barker's death, when Keilbaugh held a vigil on the corner of Second Avenue and I Street. Speaking to the city via news cameras, Keilbaugh remembers her admonishment: "You need to work with our community groups."

That same week, Mohamed was shot and protests erupted. (Mohamed's shooting was also deemed justified, on grounds that he was allegedly attacking a homeless man with a broom handle.)

Faith in the police plummeted, but the incident also inspired the city to implement a system where citizens could dialogue with police and help shape policy.

In early CAG meetings, Keilbaugh routinely sought better training for officers. "I would bring it up over and over and over again. They would kind of look at me, and it was like crickets," she says. Specifically, Keilbaugh pushed for Arbinger training, which focuses on de-escalation and communication. "And then one day, they said, 'We're doing Arbinger training,'" she says. It was a breakthrough moment.

The group compiled a list of requests: implicit-bias training, program a complaint button on the PD website, keep better statistical data on arrests. And the police responded. The site lists the CAG recommendations and their statuses.

In the intervening 18 months, training and policy tweaks led to concrete improvements, according to CAG members, and the meetings were the catalyst.

"We have implemented a lot of training that is nationally-recognized and follows the 21st Century Policing model," Brown says via email. "These include Blue Courage, Arbinger, and Fair and Impartial Policing, to name a few. We also use scenario-based training that is reactive to what the officer does, so it is dynamic and unpredictable. This better mirrors the reality we operate in and gives the women and men the tools to respond."

Among the participants was Jana Tucker, whose son Joseph was fatally shot by police in 2009. Citing policy changes, Tucker praised the top brass. "There are some nights where it gets really heated and Chief Brown takes a lot of flak, but I feel like he's honest with us, overall," she says.

By the time summer 2017 rolled around, the police department had experienced a period of relative calm. Many CAG regulars were satisfied with new-officer training, and they appreciated hearing that cops on the beat were formally recognized for their level-headedness.

"When Chief Brown tells me he gave 10 de-escalation awards away, to me that's 10 lives," says Lex Scott, organizer of Black Lives Matter of Utah, founder of the United Front and a CAG regular. "Those are officers that he says had the legal right to shoot someone and chose not to use their weapon. To me, that's 10 lives that have been saved by the CAG."

Keilbaugh holds the same view. "If I can keep someone else from losing a loved one, like James, then I feel like my time there is worth so much," she says.

CAG members began discussing ways to reach other Utah police departments and foster the same community dialogues. Things improved to such a degree, the members asked themselves whether scheduled meetings with police were still necessary. The CAG, according to some, became quiet and uneventful.

"And then the nurse Wubbels thing happened," Tucker says. In late July, Alex Wubbels, a nurse at the University of Utah Hospital, was wrongfully detained by police for sticking to hospital policy that prohibits medical staff from releasing blood samples without a warrant or the patient's consent. The community was outraged.

The next CAG meeting went off the rails, says Tucker, who is in charge of keeping the minutes.

Then, after the fury over Wubbels' arrest started to subside, the Harmon footage was released, and many viewers were adamant that the officer didn't need to fire his weapon.

To some, the recent blemishes indicate the CAG demands aren't working, while others see these as blips in a system that is slowly but steadily correcting itself.

Jennifer Seelig, senior policy advisor for the mayor and director of community empowerment, is preparing to speak to the CAG at an upcoming meeting about expectations. Understanding what members want determines whether the CAG is hitting its mark.

"If you go in there and hope to solve problems so that there isn't any more tension, I don't think that is realistic," Seelig says. "Democracy is messy."

Overall, she believes the CAG has been positive for the community. "I think that no matter what area of government we're in, we always need to be focused on where things are going and looking toward the future," she says.

Detective Greg Wilking appreciates that the CAG allows police to see the department through the eyes of the community.

"For us, it's good to hear from people who are concerned about our service," he says. "This allows for that to happen, this is a vehicle for that. Any time that we think we're doing it 100 percent right, we're probably not. If you think that you know everything, you don't. To have that engagement with these groups is beneficial."

- Body-cam still from the August 2017 routine stop of 50-year-old Patrick Harmon.

The Harmon Effect

Not all the demands are feasible, Wilking says, but many are.

Police also find it useful to be able to explain why they do some things and don't do others. Why not use Tasers? Why couldn't Harmon be disarmed? Why not aim for his legs? Wilking says those are all risky options that aren't guaranteed to stop a suspect and could put an officer in harm's way if the danger is imminent.

"I don't think there is anything we can do or CAG does that can have an effect on whether or not a guy pulls a knife on us," he says. "That is the dynamic that the individual presented to us."

It took two months after Harmon was shot on State Street for Gill to announce he was declining to charge the officer. Later that same evening, police released to media, including City Weekly, body-cam footage, the contents of which spread virally, precipitating outcries that resonated across the nation.

Three officers were on scene, and each captured the escalation from slightly different vantages.

Patrick Harmon was approached by police after he allegedly crossed several street lanes on his bicycle. Police determined that he was wanted on a felony warrant. The footage begins with a haggard Harmon holding a cigarette between his lips. It's night, and Harmon is flanked by officers, who ask him to remove his backpack.

Harmon puts his hands behind his back, but in a split second, before police can slap on handcuffs, he bolts. Harmon shoves one officer to the grass, then runs in the opposite direction. Immediately, officer Clinton Fox screams out, "I'll fucking shoot you!" and then fires three rounds in quick succession.

Motion of the camera renders the pertinent moments difficult to decipher.

Later, each officer would tell an investigator they heard Harmon utter a threat, possibly alluding to a knife. Many commenters found this detail dubious. Where was the danger? They couldn't see a knife nor hear Harmon say a word.

The following day, after the footage was posted online, Newsweek ran a piece with the headline, "Footage Shows Moment Salt Lake City Police Shot Black Man In The Back." In the same vein, CNN's web-story headline a few days later read: "Body cam footage shows Utah police shoot man as he runs away."

The question hanging around all the turmoil was how the DA deemed the shooting of a fleeing man justified.

At the CAG meeting, however, Gill explained that the evidence, though hard to discern at first, suggests something else, and he was prepared to go through it all with whomever was willing to listen. In a couple still frames, the victim's feet can be seen turned sideways, he noted. This suggests that Harmon wasn't running north, away from the officer at the moment he was shot but had instead turned his body back toward the police. And the autopsy reveals that two bullets entered Harmon's hip—not his back—and traveled from left to right, Gill said; the third bullet passed through his arm. Gill paused one section of footage from a police officer who approached Harmon immediately after he fell to the ground and handcuffed the bleeding man.

"Right there," Gill said pointing to the corner of the screen. "As he's lifting the hand up, you can see the knife off to the side."

In its totality—the knife collected at the scene, statements from the police, the appearance that Harmon had turned back toward the officer and considering the legal framework—the shooting was justified, Gill said.

At least one attendee saw the shooting in a different light. Michael Clára, a former Salt Lake City school board member, went into the meeting ready for a fight. "I didn't believe you, and I spent a lot of times calling you names," he told Gill. But after the district attorney described his process, Clára thanked Gill and said he wished that he'd heard his side sooner. "I wasted some time at some protests over the last month or so," he declared.

Not everyone agreed with Gill's conclusions, and said as much. Scott pleaded with the district attorney to lay out cases such as Harmon's before a jury and let them decide which shootings are lawful. "You are not a robot. You made the wrong call here. What you did was not right, and you need to start giving us justice," she said.

Homeless advocate and CAG attendee Bernie Hart wondered whether the recent shooting invalidated the cops' celebrated training. "We sat here week after week, many of us, and heard the same thing about how wonderful the training is and how many medals they've passed out, and they're forever patting themselves on the back," he said at the CAG meeting. The Harmon footage, he notes, shows one of three officers quickly grabbing his gun.

And while the CAG offers police the opportunity to explain their actions, some say that's not good enough. Jacob Jensen is Utah Against Police Brutality's CAG liaison, and he finds it odd—considering public officials' skill in the art of explaining things away—to simply ask, Why?

"It seems to me like the way to go is for you to have a complaint and/or a demand and for them to accommodate it," he said. "Because if you're looking for a reason behind everything, every arm of the government has a rationale for what they're doing."

UAPB is dogged in its pursuit to change policing, and nudging police to be more thorough in their training isn't going to cut it, he says. The ultimate goal, Jensen says, is to enact a community control review board.

"If you think CAG is going to promise you police accountability, it's not," he says. "If you think that CAG can offer slightly better training and slightly better representation in the police force, then yeah, we've accomplished that," he says, adding: "If you look at the CAG materially, in terms of what it's actually accomplished, it's very little."

A community control review board, as Jensen envisions it, would correct policy, discipline officers and ask the DA to file charges. It would function as an oversight board, independent of the criminal-justice system.

- Sarah Arnoff

Power of Protest

Less than a week after police released body-cam footage showing Harmon's death, local Black Lives Matter members filled a University of Utah classroom for a formal two-hour meeting. Despite the recent commotion and national media clamor, the gathering was calm, even sociable. The BLM leaders stuck to an organized agenda: Leader Scott talked for a moment on the importance of black voices speaking for Black Lives Matter. Next, another woman, Rebecca Hall, gave a brief history of the Constitution-framers' three-fifths compromise and invited attendees to learn more at a gathering she was hosting that month. Later, members split into various committees.

The prison committee, for example, decided to send holiday cards to inmates of color, while the media committee encouraged folks to simplify statements given to reporters ("They're going to misquote you," Scott said. "Don't freak out."). Another committee announced a white-ally training session, and the election committee tossed around the idea of developing a report-card rubric to grade each state lawmaker with an A-F letter.

When it was the police transparency and accountability committee's time to share, about 10 members congregated at the front of the room. A young black woman reiterated the short-term objective: Pressure the city to change its policy on body-cam footage. Activist groups, including BLM, were pushing for a mandatory 24-hour release.

"Long-term, we are hoping to [establish] civilian review boards," she said.

The meeting concluded with general housekeeping announcements, punctuated by Scott calling Jacob Jensen to the front of the room to divulge what she jokingly described as "secret things"—about a senior official in the Biskupski administration.

Around 7 a.m., Jensen said, the mayor's office had contacted him to discuss the statement they made about Harmon's death, which Jensen had criticized online.

"Through the Community Activist Group (CAG)—which began two years ago and includes members of Black Lives Matter, Utah Against Police Brutality, Copwatch, and other activists—the Salt Lake City Police Department has already begun important dialogue which has produced real results," the statement reads in part. "These include considerable efforts focused on de-escalation training, and building great community-police connections. My office has also been working on a policy governing the release of body camera footage of critical incidents."

Jensen expected a compromise on the body-cam policy, one that would inch toward UAPB's benchmark, but one they still found inadequate. Instead, Jensen described the mayor's response as "kind of pulling a Trump thing" by saying there were multiple viewpoints—an allusion to the president's words following a notorious and violent White Nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., earlier this year.

"And then she promoted CAG a lot and said that we get everything done there," Jensen recalled at the BLM meeting. The exact organizations the mayor named, Jensen noted, were those holding protests, fueled by anger at the police.

"Raise your hand if you've been to CAG," Jensen asked the attendees. A few palms floated upward. "And raise your hand if you've been to the protests, protesting things we couldn't win in CAG," he said, and triple the number of arms shot up with gusto, confirming the notion that despite the gains, those who relentlessly watch the police and demand accountability, were not ready to yield.

"K," Jensen said to the erect arms in the room. "Just making sure."

If protest spurs change, the city's body-cam footage might be the most obvious example, Jensen says.

- Sarah Arnoff

- Jacob Jensen

10-Day Rule

The sun glared on a podium beneath red and yellow autumnal leaves, where Salt Lake City Mayor Jackie Biskupski squinted back to the news cameras and reporters who had been beckoned to the Salt Lake City and County Building for a policy announcement on Oct. 17.

Noticeably absent were the organizers who had been aggressively calling on the city to enact a new rule, a fact they would go on to gripe about later.

Biskupski had just signed an executive order that would make police body-camera footage a public document 10 days after an "officer-involved critical incident" unless the investigation involved "unusual or unforeseen circumstances."

"Government should always strive to be responsive to the needs of residents while holding to values such as due process," she said. "I believe this carefully balances the need for transparency while providing for due process for investigations."

Standing 20 feet to her right, Chief Brown listened.

Gill spoke next, echoing the mayor's sentiment: "From the district attorney's perspective, our commitment, we share with the mayor, which has always been about transparency, getting this information out to the community as soon as possible while at the same time making sure that the critical aspect of investigative work needs to be done," he said.

Asked whether the protesters had influenced the process, Biskupski said the city had been working on the policy for more than 10 months.

Jensen and others found the timing suspect. "It's no coincidence that the mayor announced her policy today," he said later that evening, standing a stone's throw away from the spot Biskupski had been a few hours before. He was addressing 100 or so protesters who rallied before the city council meeting, complete with signs and slogans.

Activists took turns riling up the crowd. The voice of one participant, Oscar Ross Jr., boomed from a PA system and ricocheted off the building's scaffolding, audible a block away. He wore a red jersey, Colin Kaepernick, the former NFL quarterback who quietly protested racial injustice by kneeling during the national anthem.

"Black Lives Matter!" Ross yelled. "Patrick Harmon's life matters!"

The protesters proceeded into the city council chamber, where dozens took turns expressing their outrage. Calling the mayor's policy insufficient—one even likened it to spitting on Patrick Harmon's grave—they called on council members to draft an ordinance that would mandate police-cam footage be released within 24 hours.

- Sarah Arnoff

Unavoidable Escalation

De-escalation practices aren't a panacea. Brown and Gill highlight the fatal interaction with Michael Bruce Peterson in a gas station parking lot on Sept. 28 as case-in-point. Responding to a report of assault at a local business, officer Gregory Lowell spotted the suspect, Peterson, and attempted to question him, but Peterson defiantly walked away. When he hopped in another person's vehicle, Lowell tased Peterson, which then enraged the suspect, who jumped out of the car and began wailing on the officer.

Lowell pulled out a baton but lost his grip. Reaching toward the pavement, Peterson picked up the weapon and started hammering Lowell who scrambled away as backup, Lt. Andrew Oblad, arrived.

Oblad was able to draw Peterson's attention, but when Peterson continued to charge, the lieutenant volleyed off a round of bullets, then another round. The officer would later say he thought Peterson was wearing body armor because the bullets failed to stop him. By the 10th shot, Peterson fell to the ground, dead.

Announcing the shooting justified at a press conference on Oct. 25, Gill played Lowell's body-cam footage, as well as surveillance tape and a clip captured by a bystander.

Brown, also in attendance, said Lowell's response was exemplary. "Greg Lowell, when he showed up on that call, tried to use every level of de-escalation he could," Brown said. "From his mere presence, to trying to engage this person in conversation. He followed at a safe distance. He went to a Taser to try to stop the aggressive actions of this suspect. And then, unfortunately, he went to an impact tool [a baton] and that was forced against him. I commend officer Lowell."

The tragic end, he concluded, wasn't the result of poor training.

- Sarah Arnoff

Out of the Dark

In the Dark Ages, when Western civilization sank into an unenlightened morass, a studious monk hunkered in a cramped, dank cell and by candlelight dutifully copied an obscure Aristotle text—at least that's how Gill likes to imagine history unfolded. In Gill's mind's eye, this monk toiled away at his task, translating each sentence from Greek to Latin despite knowing that a majority of his community was illiterate. The payoff was questionable, certainly imperceptible. Regardless, he continued, and in doing so, kept that work alive, to be inherited by citizens who lived centuries after the monk died.

As the CAG meeting wound down, the conversation broadened to one about the plodding pace of democracy, the necessity of citizen empowerment and the forces that drive folks to feel alienated.

"Democracy is hard work," Gill said at the CAG meeting. "It requires people to be engaged. It requires investment of time, and it requires showing up even when you're losing. That's what the price of democracy is because people get apathetic."

He and others see the CAG as one small but significant investment.

When Tucker lost her son Joseph in 2009, the CAG didn't exist; she had no direct lines to officials. In an age when public discourse often feels like disagreeing parties are merely screaming in opposite directions, direct dialogue is vital, she argues. That alone is worth preserving.

"We're going to keep at it, I guess," she says. "Some nights I just think, 'I can't go there.' I come away with such a headache when we get done, no matter what we've just discussed, and I don't know if I can go again next time, but we all keep showing up and trying to maybe affect a little bit of change."

Scott has noticed resignation among some of her peers. They see no clear path out of the opaque Dark Age, growing numb and inured as they wait for signs of progress, so they give up. But Scott refuses to accept it. As a mother, she's spent too much energy on the cause to bequeath to her 10-year-old child the same burden.

"I see activists drop off because they want change so quickly," she says, then adds, "The buck stops here, man. I work really hard. I'm not playing around, and when I said I'm going to change the world, I am."