- Derek Carlisle

History hasn't been kind to Lloyd Eaton. In nine seasons as head football coach of the University of Wyoming, Eaton led the Cowboys to eight consecutive winning seasons and three conference championships. But when Eaton is rememberd these days—if he's thought of at all—it's not for his record as a gridiron innovator who knew how to make teams win. Rather, it's for his complicity in prejudice.

On Oct. 17, 1969, 14 of Eaton's African-American players came to his office with a concern. The all-white team they were scheduled to play the next day was Brigham Young University—a school owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which actively and openly discriminated against blacks, barring them from equal participation in church rites and relegating them to second-class status.

The Black 14, as they came to be known, sought Eaton's permission to speak out against BYU's policies. He didn't even entertain the conversation. Protests were against team rules, he declared—and summarily kicked the players off the team.

News of Eaton's action ignited a national conversation about whether upstanding universities should engage in sports competitions against schools that discriminate. In the following months, university sports programs across the nation were pushed to boycott BYU. Some did so publicly, others tacitly. Many simply ignored the criticism, reasoning that the football field wasn't the right place to take a stand against racism.

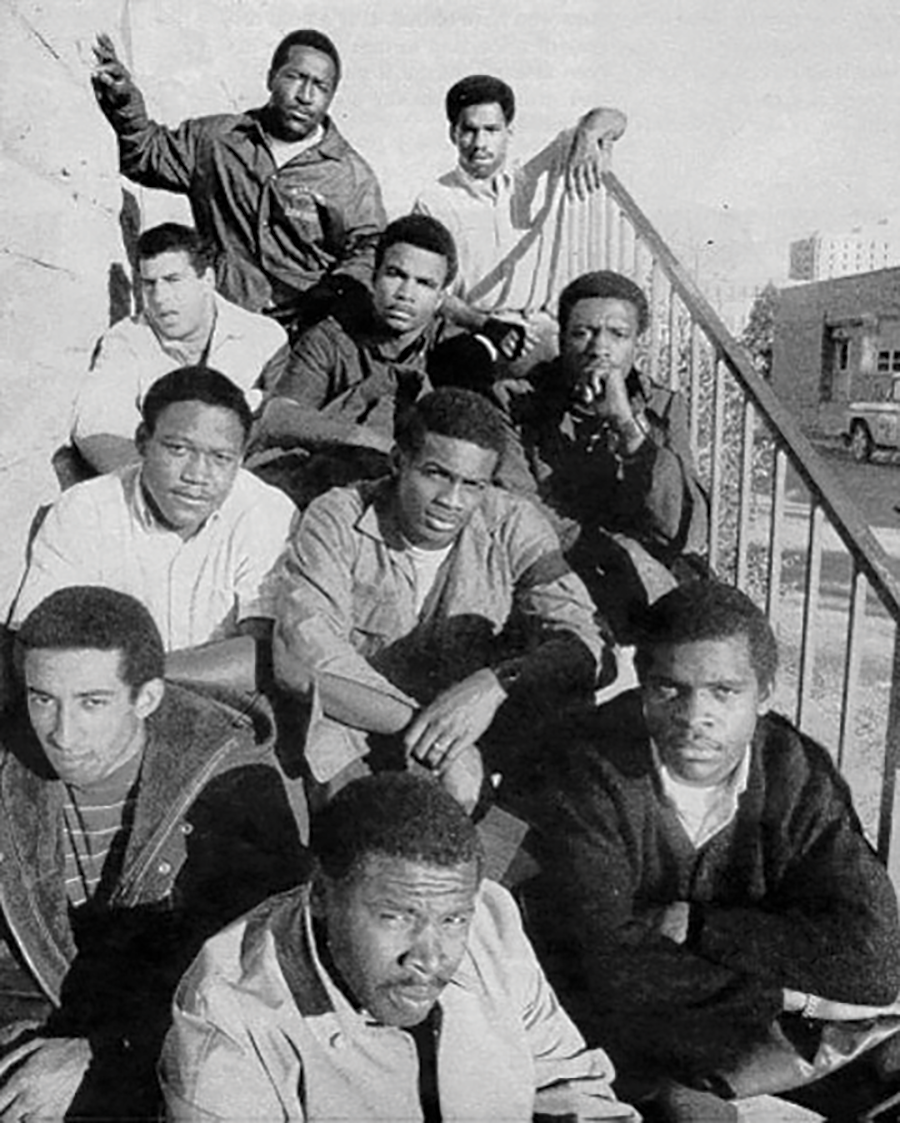

- UW American Heritage Center

- Members of the Wyoming 14.

Everything that's old ...

As the 2019 college football season begins, University of Utah and Utah State University players, coaches, athletics officials and fans once again have an opportunity to take a stand against prejudice. And at the center of the issue, just as it was 40 years ago, is BYU.

The LDS church—often called the Mormon church, although its leaders have recently abandoned that nickname—officially ended its racist policy in 1978 when black men were allowed in its priesthood. But the church and its flagship university weren't done with discrimination. At BYU today, a so-called "honor code" specifically bans from the university students who engage in acts of physical intimacy with people of the same sex, even when those acts are completely non-sexual. Gay students worry they can be expelled for things that heterosexual students don't have to think twice about, like holding hands in the quad, cuddling in the student center or sharing a kiss at the campus duck pond.

And although same-sex marriage has been legal in Utah since 2013, two years before it was federally legalized by the U.S. Supreme Court, even students in legally sanctioned same-sex marriages are banned from studying at BYU. Such marriages, the school argues, are "sinful and undermine the divinely created institution of the family." Straight students, meanwhile, can marry at will, and they do so in droves.

Under current U.S. law, private institutions that receive federal funding can claim a "religious faith" exemption to Title IX, which famously provides women with equal access to educational services but has been expanded in recent years to protect LGBTQ students. BYU has a legal right to discriminate.

But some LGBTQ rights advocates believe other universities should be grappling with the same questions that faced their predecessors after the Black 14 story put the LDS church's racial prejudice into the national spotlight 40 years ago.

Instead of answering those questions—or even asking them—universities across the nation are lining up to do business with BYU. A review of dozens of contracts between BYU and the schools it has contracted to compete against on the gridion shows millions of dollars changing hands between institutions with strict non-discrimination rules and a university that openly and actively discriminates against LGBTQ individuals.

Ready for some football?

Utah plays BYU on Thursday, Aug. 29. Utah's non-discrimination policy commits the Salt Lake City-based school to "providing and fostering an environment that is safe and free from prohibited discrimination."

Utah State faces the Cougars on Nov. 2. "In its programs and activities," USU promises in its policy that it "does not discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation or gender identity/expression."

No school can make rules for another, of course. But institutions of higher education can choose the conditions under which they will do business with others. Indeed, Utah's standard independent contractor service agreement commits anyone doing business with the U to adhere to the school's nondiscrimination policy.

Under that standard contract, the University of Utah likely could not hire a janitorial company to sanitize Rice-Eccles Stadium if it refused to employ people who are in gay relationships. Following similar rules, Utah State couldn't hire a concessionaire to sell hotdogs at Maverick Stadium if that company fired people for getting married to someone of the same sex. If either school tried to staff its football games with a security firm that maintained the same policies as BYU, the contract would, under the terms of both schools' policies, likely be turned down.

But the contracts with BYU don't include a non-discriminiation clause. Thus, the state's two most prominent public universities can do business with a school that encourages students, faculty and staff members to report on members of the college community who are suspected of homosexual behavior and other honor code violations. (There's even a convenient web form to make things easy for snitches.)

"I've had friends kicked out of BYU for being queer," says Christa Cannell, a board member at Logan Pride, which advocates for LGBTQ students and other community members in Logan, the town where Utah State University's flagship campus is located. "That's a very real and very harmful practice."

Cannell laments a social environment that allows discriminatory organizations of all sorts to continue doing business as usual without fear of repercussions.

"Unfortunately, being anti-queer in America isn't a 'bad enough' thing yet to, say, justify turning down an organization or turning down money," she says. "A lot of organizations actively donate to anti-queer causes and other organizations do business with them all the time."

In the midst of all of the problems faced by queer students at universities across the nation, Cannell says, a football game against BYU probably isn't on a lot of people's radar.

"Non-allies don't likely care. Allies probably don't see it unless it's pointed out," she says. "The priority is football and entertainment. That's the status quo. I'm not sure what would need to happen to change that."

A complicity of choice

Being gay isn't a choice. Playing football against BYU is. While both Utah and Utah State have a long tradition of competing against BYU on the gridiron, neither is bound to do so. BYU isn't in the Pac-12, like Utah, or the Mountain West Conference, like Utah State. In fact, BYU football isn't in an athletic conference at all. It has been independent since the 2011-12 season. And although it has openly sought to join a conference since then, the university's record on gay rights is one of the factors that seems to have prevented the major conferences from asking BYU to join.

In 2016, when the Big 12 appeared to be entertaining the idea of inviting BYU into its ranks, 25 LGBTQ advocacy organizations signed onto a joint letter urging the conference to think twice. "As organizations committed to ending homophobia, biphobia and transphobia both on and off the field of play, we are deeply troubled by this possibility," the letter stated. "We feel it would be extremely problematic to include BYU in your conference expansion."

The invite from the Big 12 never came, and no other major conference has shown any public interest in BYU. That means that BYU can't rely on a conference to set its schedule. When universities do compete against that school in football, they do so as the result of a voluntary and independent negotiation for revenue sharing.

Those universities could do what the Big 12 did, simply declining to do business with a university that discriminates. In doing so, in many cases, such schools would simply be following the rules they have set for doing business with any other entity. But that's not happening.

Hudson Taylor, the executive director of Athlete Ally, an LGBTQ advocacy organization that helped push the Big 12 to reject BYU, isn't surprised by the disconnect between the stated principles of individual institutions and their practices.

"There are a lot of schools within the NCAA that are supportive of their LGBTQ athletes and fans, but that isn't necessarily evident through their actions, such as who they play," he says. "There is still a culture of looking the other way."

Money ball

This year marks the 100th playing of the "Holy War" between BYU and Utah, and the 89th meeting between BYU and USU, a game played for the honor of hoisting "the Old Wagon Wheel" trophy.

While the inertia of history is strong, both Utah and Utah State have had BYU-free football schedules in recent decades. Most notably, Utah refused to play BYU in 2014 and 2015, showing a willingness to snub its long-term archrival when it was in its competitive and financial interests to do so.

Utah fans were divided on that decision. Some cheered the brush-off as the ultimate spiking of the football over an inferior opponent. Others lamented the end of a long tradition. Few entertained the question of whether, as a public institution of higher education committed to non-discrimination, Utah should be playing BYU at all.

Rob Moolman, the executive director of the Utah Pride Center, thinks it's time to have those conversations.

"I understand the history and the importance of BYU in Utah, particularly, but I wonder about the choice to play BYU," he says. "I wonder about the decision-making, because the decision to play BYU indicates that the schools' officials believe LGBT representation is not important. It seems like it's a secondary or minor issue that they don't want to consider."

The state's two most prominent public universities have spoken forcefully in favor of LGBTQ rights on campus. But Moolman says actions will speak louder than words.

"I'm not sure if these schools understand the message they're sending to our community, to our members, when it looks like they're ignoring these issues entirely," he says. "The message is that the games are so important to our culture, to our way of life, that they're willing to look the other way about the impact it's having on a marginalized community ... it looks like their university is celebrating the decision to play BYU, when BYU is minimizing queer identities."

While Utah and Utah State are the two teams with the longest history of competition against BYU, they aren't the only institutions that have roundly ignored that school's anti-gay policies. It takes a lot of schools to fill out a football schedule, after all.

And it takes a lot of dough to make that happen. For coming to Provo to play football at BYU, other schools usually get a check for $250,000. BYU generally gets a similar part of the take when it goes on the road, according to contracts.

That quarter-million payout is the same deal BYU has with Utah. At Utah State, the teams forego the exchange of payments, covering all their own expenses one year while reaping all of the rewards the next year.

Such home-and-home contracts are typical between schools of similar sporting merit. But, like many large sports programs scheduling non-conference opponents, BYU pays larger "body bag" fees to schools that agree to come to Provo for a likely whooping. It has agreed, for instance, to pay Utah's Dixie State University, another public university, $425,000 for a game scheduled for 2022.

Such arrangements work the other way, too. The University of Oregon will put $1.1 million into a BYU account to get the Cougars to come play football in Eugene in 2022. That's despite the fact that Oregon typically requires both contractors and subcontractors to not only commit to non-discrimination but also to "take affirmative action to employ and advance in employment individuals without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability or veteran status."

That doesn't sit well with Liz Sauer, the communications manager at the LGBTQ advocacy organization Basic Rights Oregon.

"It's really curious and, frankly, disappointing that the University of Oregon, which has generally done quite a good job of supporting LGBT equality, has gone out of its way to support and play BYU when it has such discriminatory policies," she says. "I would hope the university is open to criticism and open to discussion with the community on its policies."

Sauer wants Oregon to answer some basic questions about the contract it signed.

"Like, why is this the case? Why is it important? Since BYU is not in the same conference as the University of Oregon, and they're not required to play them, what is the point? What's their purpose here?" she asks. "I would hope they listen to students and the community on why BYU's policy is problematic to students."

She hopes Oregon students, faculty and staff consider how to respond.

When people "come together as a community and say, 'No. No more. Not on my watch,' it's one of the most powerful actions you can take," she says.

If that were to happen, maybe athletics directors would think twice before signing contracts like the one Oregon athletics director Rob Mullens put his signature on in 2015, committing to a game seven years in the future against a school with a long history of discrimination.

Mullen's top spokesman, Jimmy Stanton, declined to address the seeming hypocrisy that exists when a school refuses to sign contracts with institutions that aren't actively committed to non-discrimination, but ignores that policy when it comes to football. He notes that BYU has scheduled games with other Pac-12 opponents, too, "as they are a strong non-conference opponent within the region."

Oregon, Stanton says, has "a strong culture of inclusivity and diversity," including the BEOREGON campaign, which "encourages all Ducks to be their most authentic selves." He declined, however, to address the fact that his university has agreed to pay more than $1 million to a school where student-athletes can't be their authentic selves.

But at least a representative from Oregon said something. Officials from Utah and Utah State refused to comment on the issue at all.

Playing dumb

With a devoted national following of members of the LDS church and a long-term television contract with cable sports giant ESPN, BYU is an enticing opponent for athletics directors looking for a chance to raise their program's profile.

"When we compete against BYU, it's not an everyday matchup so I think it's going to help with our brand," says Tom Kleinlein, the athletics director at Georgia Southern University, which will trade payments of $100,000 with BYU for games in 2021 and 2024. "People are going to pay attention to us."

- Ray Howze

As for BYU's discriminatory practices? "I've never really had an issue with it," Kleinlein says. "I don't live in a world where I am very judgemental of other people's policies."

The University of Toledo's athletics director, Mike O'Brien, called BYU "a great name."

Does a "great" school treat straight and gay students differently? "I am not going to go down that route," O'Brien says. "We signed a contract ... That has several parameters. We are abiding by what is in the contract, as is BYU."

O'Brien argues the contract was "done many years ago." It was, in fact, signed in 2015—and he was the person who signed it. Pressed to explain why he would sign a contract with a school that openly and actively discriminates, O'Brien hung up the phone.

Taylor, the Athlete Ally executive director, says "football, not politics" is a recurrent excuse for not standing up to prejudice.

"I think one of the first things you hear is, 'Stick to sports,'" he says "There is a common response to diminish or ignore how culpable an individual or institution is when it comes to LGBTQ bias, bullying and discrimination."

Not every official is resistant to introspection, however.

Ryan Bamford, the athletics director at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, which ends a four-year, $250,000-per-game contract with BYU this season, says such a deal "is about trying to fill a schedule. We try to get two what we call 'Power Five' teams, so those are usually on the road, one-for-ones, basically to make money."

(Although BYU isn't in one of the Power Five conferences, universities from several conferences count the Provo school as a Power Five opponent for the purposes of scheduling.)

Bamford compared the decision to play against BYU with a long-term contract UMass had for football games against Liberty University. That school's founder, Jerry Falwell Sr., and its current president, Jerry Falwell Jr., share a history of homophobic and transphobic rhetoric. "The values of a school don't really weigh in," Bamford explains. "Unfortunately, we don't take those things into account when we are building our football schedule."

Bamford says he would explore the legal ramifications of the contract. "It could be an issue going forward," he says, "if it flies in the face of Massachusetts state policy."

But what if it's not a legal issue? What if it's just a moral one? "It is certainly food for thought," Bamford says. "That's something we have not yet considered, but something we should consider in the future."

That might be easy for UMass; its four-game contract with BYU ends this season. For other schools, getting out of a game could be more complicated, and more costly.

When the University of Missouri entered into a contract with BYU in 2014, it agreed to not only exchange payments for a home-and-home series of games, but to underwrite the costs for a hapless football program from Wagner College, in New York, to travel to Provo for a body bag game in 2015. That essentially guaranteed that BYU would have an extra win on its schedule when it faced off against Missouri a few weeks later—a bit of system gaming that is increasingly common in college football schedule making. (Indeed, Wagner lost 70-6 in its mismatch against BYU.)

Since BYU played in Kansas City in 2015, "we owe them a game," Nicholas Joos, Missouri's deputy athletics director for communications, points out. "It would cost us a lot to get out of that game."

How much is a lot? The cost of breaking up with BYU, as dictated in the terms of most of the contracts, is a million bucks.

BYU's schedule this season includes Utah, Utah State, Toledo, UMass, Liberty, the University of South Florida, the University of Tennessee, the University of Southern California, the University of Washington, Boise State University, Idaho State University and San Diego State University.

Of those schools, Utah, USC, Boise State, Utah State and Idaho State have multi-year contracts with BYU. So do Arizona State University and Stanford University, which are scheduled to start squaring off against BYU in 2020, and Baylor University, which has a home-and-home agreement with BYU that starts in 2021.

The Washington, Arizona State, and Stanford games are particularly ironic. Those universities were part of the coalition of institutions where students and faculty protested against their schools' decisions to enter into contracts to play against BYU in the 1960s and 1970s. Some schools continued to ignore BYU. Despite the fact that both universities are private schools in the western United States with storied football programs, Stanford didn't play BYU in football until 2003.

Big cover

The National Collegiate Athletics Association scored a significant public relations victory in 2016, when it threatened to pull its championship events from North Carolina over that state's infamous anti-trans "bathroom bill." And yet, as Cyd Zeigler of Outsports pointed out at the time, the NCAA continued to turn a blind eye to the "far more sinister and discriminatory" policies affecting LGBTQ athletes and other students at BYU.

NCAA officials can't argue, as many athletics directors did, that they simply didn't know about BYU's discriminatory policies. In 2017, the director of the NCAA's inclusion office, Amy Wilson, visited BYU "to discuss ways to create more inclusive and respectful environments and experiences for NCAA student-athletes and staff of all sexual orientations, gender identities and religious beliefs." Even then, Wilson avoided direct criticism. And since then, the NCAA has remained silent about BYU's treatment of LGBTQ students and faculty.

But if the NCAA is looking for cover for its habitual turning of blind eyes, it doesn't have to look far.

When Nike's new corporate code of conduct was released in May, the company's chief ethics and compliance officer, Ann MIller, wrote that all Nike employees should be "guided by both the letter and the spirit" of a code that expressly prohibits discrimination, not just among Nike employees, but also "colleagues, visitors and partners." A slide presentation created to publicize the code proclaimed "we choose who we do business with carefully."

A few months later, the athletic giant won widespread praise for its pro-equality "Be True" campaign, including a commercial with a voiceover from triathlete Chris Mosier. "None of us can truly win," Mosier said in the video, "until the rules are the same for everyone."

Yet when Nike signed its latest licensing agreement with BYU, the company was silent about the fact that, at BYU, the rules are absolutely not the same for everyone.

Rather than speaking out against discrimination, the company's famous founder, Phil Knight, slathered praise on BYU. "We don't have a better relationship in the country than the one we have with BYU," Knight said in a statement. "We are very proud of it. We love the relationship and the program."

Nike spokesman Josh Benedek repeatedly declined to explain how a company that markets itself as a supporter of LGBTQ athletes could be proud of a relationship with a university that openly and actively discriminates against gay athletes.

But Nike isn't alone in that sort of duality.

ESPN makes it clear to advertisers that it won't permit discriminatory messages to be broadcast on its networks. The Walt Disney Company-owned sports network has also taken action to punish discriminatory language on its channels; in 2016, it fired commentator Curt Schilling over transphobic comments. But in 2010, the powerful cable network inked a muti-year contract to broadcast BYU football games—not only putting that school in the national spotlight but giving other teams a powerful incentve to ignore BYU's discrimination in exchange for a piece of the exposure.

In a statement during his school's annual football media day, athletic director Tom Holmoe credited the ESPN contract for BYU's ability to line up a strong home schedule, according to a report in The Salt Lake Tribune. ESPN has also played a hand in getting BYU into bowl games that the school would otherwise have been passed over for—making arrangements, for instance, for 6-win-and-6-loss BYU to play in the Famous Idaho Potato Bowl in 2018, even as other teams with similar records were left out of postseason play.

Holmoe says an extension to the school's contract with the network, originally set to run from 2010 to 2018, is being negotiated. "We plan to be with ESPN for a long time," he says.

ESPN officials declined to address their network's role in providing exposure to a school where a gay football player would risk expulsion for celebrating a win with a kiss from his boyfriend.

Bad actors

BYU associate athletics director for communications Duff Tittle says that, at his school, "we strive to treat all members of our campus community and those who visit the school with respect, dignity and love."

That's all he would offer in response to the notion that his school has been signing a lot of contracts with institutions that maintain strict non-discrimination policies.

- Ken Lund

BYU certainly isn't the only institution of higher education with discriminatory policies in place. LeTourneau University in Texas has banned LGBTQ student-athletes from dating. Azusa Pacific University in California pushed out its former chair of theology and philosophy after he came out as transgender. And Liberty, which is by far the lowest-profile of any school BYU plays this year, has a long and well-documented history of anti-LGBTQ discrimination—including pushing gay students toward so-called "conversion therapy" and denying equal treatment to the same-sex and trans spouses of military personel, according to the nonprofit advocacy organization Campus Pride.

But BYU is unquestionably the highest profile school in that group when it comes to college sports, and the only one competing in Division 1 athletics.

At least one BYU student athlete believes that makes her school a legitimate target for protest.

Like other LGBTQ students at BYU, Emma Gee, an openly bisexual cross-country and track runner, is bound by the school's honor code to avoid engaging in "all forms of physical intimacy that give expression to homosexual feelings."

Gee loves her team. Fellow student-athletes, she says, have been nothing but supportive. But she pulls no punches about her school's anti-gay policy: It contributes to an atmosphere of paranoia for LGBTQ students—especially student-athletes.

"Many student athletes here are very prominent in BYU's culture, so there's a lot of eyes on them," she notes.

What should other schools do to stand up to such discrimination? "I think any school that recognizes the homophobia that it is, has every right to protest against that," Gee says. "If schools were to choose to do that, it would make sense to me. Any time there are things that are unfair and not right, people need to speak up."

That pressure can come from within the school, as it has with Gee. But, she stresses, "in some people's situations, it's not safe to come out."

"As someone who is here and I see a lot of the pain, I wish things would be better," she continues. "If that is what it took—people breaking contracts with BYU, or not signing at all—that would be great."

Could that really make a difference? Not if you take LDS leaders at their word. BYU's policies stem from church dogma, and "central to God's plan," the church's website proclaims, "the doctrine of marriage between a man and woman is an integral teaching" of the church and "will not change."

Regardless of whether BYU and LDS brass ever hear from heaven on the issue of equality for LGBTQ individuals, it's clear to Athlete Ally's Taylor that they need to hear from their fellow humans.

"It is incredibly frustrating," he says. "There is still a very reactive state of mind. Institutions will do the right thing when there is enough public pressure, but to actually invest in that proactive solution, I think there are far fewer institutions actually leading the way."

Moolman says he would like to see that leadership come from the Beehive State.

"I wonder if BYU was choosing to treat people of color, or women, or our Native American population, a more visibly marginalized group, this way, I wonder would these schools still play them?" he says.

"Maybe we're on path to look at protests at BYU, or boycotts on games for universities with discriminatory practices," Moolman explains. "I hope we're beginning to see some of that mentality emerge ... I hope we're moving to a time where people will start to reassess why they continue to foster these relationships."

But with little time to go before the Holy War, Moolman has another thought.

"I wonder what if everyone at the University of Utah walked into the next BYU game with a rainbow flag?" Moolman says. "It just might change the emphasis on how communities and universities could be seen supporting the LGBT community at these events. I think the pressure universities could place on BYU is important."

Carter Moore and Kat Webb are students at Utah State University, where Matthew D. LaPlante is an associate professor in the Department of Journalism and Communication. Versions of this article are scheduled to appear this week in Oregon and Florida.