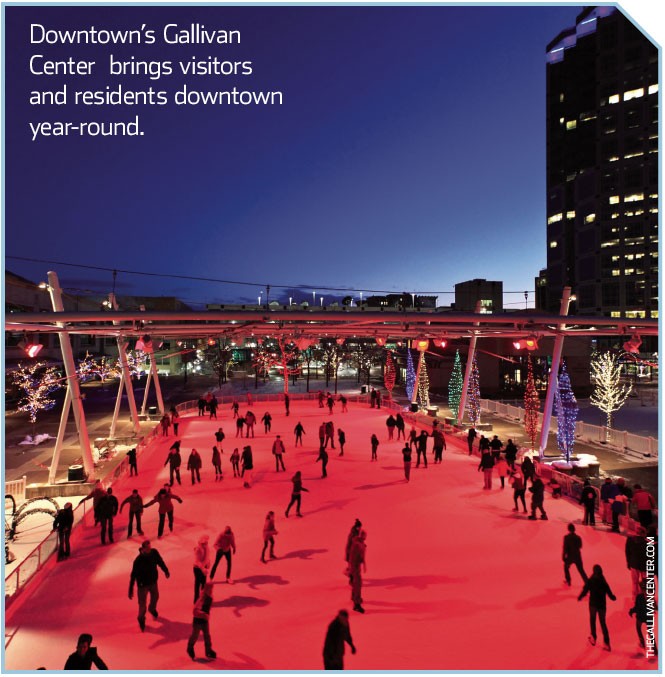

It's the holiday season, and vehicles packed with fun seekers are barreling into downtown Salt Lake City. They're coming for the twinkling lights, the concerts, The Nutcracker, ice skating at Gallivan Center, the high-end mall shopping. Some end up at City Creek Center to shop and gawk at illuminated Temple Square. Others drive to the Gateway for dinner and a concert, or to Capitol Theatre for a show.

And before you know it, traffic into downtown grinds down to a crawl. Holiday cheer becomes holiday road rage as drivers vie for parking in time for their shows and concerts. The problem? With the long gaps between shopping, dining and entertainment venues, visitors and city residents spend far too much time driving and searching for parking spots close to their destination. Not only do they assume (incorrectly) there is no place to park, but the constant shuffle adds to congestion, air pollution and a general dislike of heading downtown.

So how is it that such malaise exisits when there is so much going on downtown? Especially after Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker just spent two terms in office making downtown vitality a key priority. Under his watch, construction started on a $110 million Broadway-style theater and the 111 Main office tower.

GREENbike, the nonprofit bike-share program that was launched downtown in 2013, set a national ridership record in November 2015 compared to other programs, with the most rides per bike. Ridership has increased by 300 percent since its launch, growing from 10 stations and 55 bikes to 25 stations and 200 bikes at various downtown locations. This fall, downtown also welcomed the second protected intersection in the country where cycle tracks on 300 South and 200 West intersect.

The streets of downtown have lately filled with workers and shoppers, after the new 222 Main building and City Creek Center opened in recent years. Goldman Sachs, which occupies most of the 222 Main tower, will expand into the 111 Main tower when that project opens in the fall of 2016.

Working in concert with new development are organizations such as the Downtown Alliance, which is tasked with creating events and activities that bring people downtown. The Downtown Alliance's Eve celebration attracts around 40,000 visitors over the three-day event. The Farmer's Market at Pioneer Park brings nearly 250 vendors and 10,000 people each Saturday during summer months.

Downtown is also the host to Salt Lake Comic Con and trade shows like Outdoor Retailer that bring an estimated 170,000 visitors each year, according to estimates from organizations that stage the events.

Yet, despite the buzz and popularity of downtown, the city still struggles to create a cohesiveness and sense of vitality. While there are small pockets of synergy, many of downtown's long blocks remain empty outside of business hours. The onus of solving that puzzle now rests upon the shoulders of Mayor-elect Jackie Biskupski and the Salt Lake City Council. The Mayor-elect's plans for downtown, according to Biskupski's campaign website, include reassessing parking fees, financing more affordable housing, enhancing transportation options and lowering the costs to do business downtown. While she did not respond to calls asking for comments to this story, Mathew Rojas, spokesman of Biskuspki's transition team, said the Mayor-elect plans to make improving downtown vibrancy a priority.

The Art of Vibrancy

While, to many locals, downtown seems more alive than ever, it actually leaves room for improvement. Emil Malizia, a professor of city and regional planning at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, says that among peer cities, downtown Salt Lake scores low in vibrancy.

"Vibrant spaces are dense, diverse and connected places where you can live, work and play," Malizia said in a Nov. 5 presentation to the Utah chapter of the Urban Land Institute (ULI), a nonprofit organization that advocates for responsible land use.

To measure vibrancy, Malizia looks at the compactness, density, walkability, regional and intra-city connectivity and mixed land uses of the nation's 100 largest metropolitan areas. Salt Lake City scored below average on Malizia's downtown vibrancy index, below neighboring cities such as Boise and Denver. Both in terms of walkability and what Malizia refers to as the "18-hour downtown"—activities that draw people downtown both day and night—Salt Lake City fell short.

Downtown Salt Lake City's notoriously large city blocks are partially to blame. Making up what is referred to as the "Mormon grid," Salt Lake City's 10-acre blocks are four to five times larger than the average city block. According to Malizia, by comparison, the average downtown block in Portland is 0.92 acres while Denver's blocks average 2.39 acres. And surface parking lots that take up an entire block would be comparable to four or five continuous surface lots in other cities.

According to Malizia, vibrant downtowns aren't just more interesting, they impact the entire region. Malizia argues that metropolitan areas with a vibrant downtown boast healthier residents, have fewer car fatalities and enjoy a larger economic output.

Good urban design increases vibrancy and encourages people to get out of their cars and walk. That was the conclusion of a 2015 study by University of Utah professor Reid Ewing, along with others. For the study, researchers conducted pedestrian counts at 32 randomly selected block faces across Salt Lake County during the spring of 2012. They counted zero pedestrians at over half of the block faces. Only the downtown blocks selected had a significant pedestrian presence.

Researchers began a more in-depth study of downtown pedestrians, taking into account five urban design qualities.

The first is "imageability"—what a pedestrian sees, including trees, landscape, landmarks and signage.

The second is enclosures—buildings, trees and walls that create a room-like ambience.

Human scale makes up the third design quality, referring to the spatial arrangement between structures and people

Transparency is the fourth quality referring to the ability to see human activity within public and private spaces.

Complexity is the fifth design-quality measure. It refers to the the structural and aesthetic details that create a "rhythm" along a street.

Of the five, imageability and transparency most influenced pedestrian activity in downtown Salt Lake. A streetscape with high imageability is more visually interesting to pedestrians. Outdoor dining, display windows and large doors that open to the street contribute to transparency, pushing the energy of active spaces onto the sidewalk, which ultimately engages pedestrians.

For example, Main Street scored high in University of Utah study. "Walking on Main Street feels different from walking on State Street," said Salt Lake City urban designer Molly Robinson during an October Salt Lake Design Week downtown walking tour that looked at urban design principles.

According to Robinson, Main Street has active uses and qualities that make it vibrant and interesting to a pedestrian, while other sections of downtown discourage walking with dead space—places that offer little activity to hold a pedestrian's interest. In comparison, Robinson cites buildings, such as the Federal Reserve Bank building on State Street, that don't engage at the street level. State Street also lacks bike lanes, has a higher speed limit and has fewer trees and signage, which discourages pedestrian activity, according to Robinson.

Lots of Parking, Really

So what is the deal with parking? Are good parking places really that hard to find?

"Parking was a lot easier 10 years ago because there was less going on," says Downtown Alliance's spokesman Nick Como. The seeming lack of parking "is a sign of a city growing up and being vibrant." Quite to the contrary, "We have more than enough parking for a city of our size," Como said.

U of U researcher Ewing agrees, noting that downtown Salt Lake City not only has enough parking, it might even be "over-parked." That means that downtown development could continue to grow at its current pace for years without the need for additional public parking.

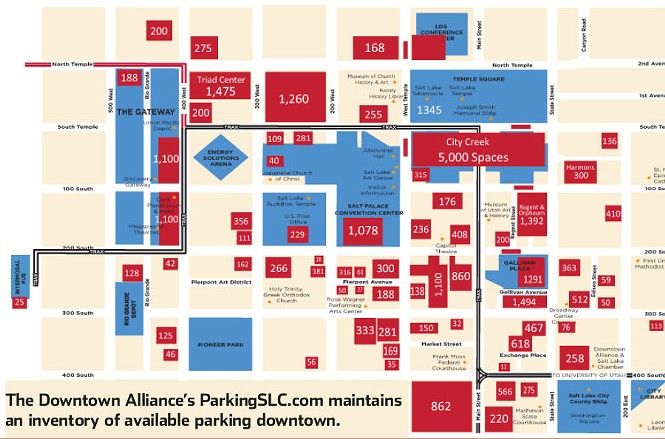

In Salt Lake City, surface parking lots are among the biggest culprits in killing downtown energy. According to estimates from Salt Lake City's Division of Transportation Planning, surface lots make up about 20 percent of the land downtown, or 55 acres (equal to nearly three City Creek Centers, or five Temple Squares). According to parking data from ParkingSLC.com, a website managed by the Downtown Alliance which compiles data from the Salt Lake City's Transportation Division, nearly half of the parking facilities in downtown are surface parking lots.

"Parking is a good thing, but surface lots are not. They are dead space," said Ewing, who is professor of city & metropolitan planning at the University of Utah. "Parking is the ultimate dead space because it replaces active space."

The city's surface parking lots, though plentiful, provide only 20 percent of available stalls. They aren't nearly as efficient as parking garages that not only hold hundreds of more parking stalls, but they can be tucked behind buildings or, if they face city streets, they can allow street-level uses.

In the past, surface lots proliferated downtown because they are cheaper than a parking garage to build and, for downtown land owners, remain an easy source of income.

"Property owners will buy up several parcels [of old buildings], then want to demolish the building, so that they don't have to pay property tax on them," said Salt Lake City Councilman Stan Penfold. "You can get a pretty good return on a surface parking lot, and you don't pay taxes like a normal business would."

In general, property taxes are higher when there is a physical structure on a lot. Buildings carry higher value than land, making it more enticing for developers to hold the parcels while waiting to sell when the land's value increases.

What's more, Penfold says, Salt Lake City can't change how surface lots are taxed because those taxes are regulated by other entities. Salt Lake County sets the rates but the state writes the tax laws. Because taxes are based on property (market) value, developers pay less property tax on undeveloped lots.

To discourage new surface lots from developing downtown, the Salt Lake City Council in 2012 passed a building ordinance prohibiting the demolition of downtown buildings to create parking lots in the downtown business district from North Temple to 700 South between 200 West and 200 East.

The 2012 ordinance prohibits surface lots and parking structures from being built on block corners downtown and along Main Street. Mid-block surface lots either must be set behind a building or set back 75 feet back from the front property line.

Penfold, who represents District 3—which includes the lower and upper Avenues, Capitol Hill and Federal Heights—sponsored the ordinance because surface parking lots exaggerate the impact of the city's large blocks by creating dead space. Surface lots also tend to discourage adjacent development.

But, Penfeld says, Salt Lake City's large blocks also give it a unique opportunity. "With our big city blocks, we can tuck parking structures in the middle of the block, behind buildings," he said.

Even though new surface parking lots are prohibited by the ordinance, developers who receive approval to demolish a downtown building only need to landscape, not build a structure, on the property.

Penfold said the city needs to encourage developers to find other temporary uses that activate a space while waiting to build new projects. Penfold cites the temporary shops and eateries built on Main Street while builders waited for market conditions to improve to construct the new 222 Main tower.

Parking Glut

According to parking data gathered by the Salt Lake City Transportation Planning Division, there are nearly 33,000 public parking stalls between 400 South and North Temple and 200 East and Interstate 15.

By comparison, based on data from the Downtown Denver Partnership, Denver has 42,009 parking spaces. But with an estimated 2014 population of 663,862 residents, Denver is more than three times larger than Salt Lake City's estimated population of 190,884. There is one downtown parking space for every 15 residents in Denver.

Salt Lake City has one downtown parking space for every 6 residents. Thus, per capita, downtown Salt Lake has more than twice the amount of parking than Denver.

Both Denver and Salt Lake City are regional job centers and have large daytime downtown populations. But even considering the 2014 metropolitan population estimates (Denver's metro has 2.7 million, while the Salt Lake City metro has 1.15 million), Utah's capital city still has nearly double the downtown parking per capita. There is one stall for every 65 Denver metro residents, while in Salt Lake there is one stall for every 36 metro residents.

The city's Transportation Division estimates that the nearly two blocks of parking under the City Creek Center—which accounts for nearly 16 percent of downtown parking—are only at 20 percent occupancy on any given day. There are 79 privately owned surface parking lots and garages downtown between 500 West and 300 East and North Temple and 500 South, 40 of which are parking garages or structures. Although those garages account for just over half of the total places to park, they represent 80 percent of the total public parking downtown.

SLC Parking Is Affordable, Too

City Weekly made inquiries with a number of parking facilities listed on the Downtown Alliance's ParkingSLC.com website. In general, most downtown surface lots charge a flat daily rate, while garages are more likely to charge by the hour.

Underground parking garages at the City Creek Center and the Gateway offer the most competitive rates. The Gateway charges $1 an hour with the first hour free. City Creek charges $2 an hour with the first two hours free and third hour free if the ticket is electronically validated. Combined, the shopping centers account for nearly one of every four parking spaces downtown.

Parking garages offer more parking, but tend to cost more (with the exception of City Creek Center and the Gateway). Prices among three of the largest non-mall downtown operators range from $1 to $4 an hour.

Downtown's bumper crop of 39 surface parking lots are easy to spot. But surface lots, even the uber-large city-block size lots, don't come close to holding the number of vehicles that can be parked in a garage. Surface lots are also priced for longer stays. According to City parking data, most surface lots downtown average around $5 per day of parking.

Not surprisingly, the LDS Church earns a pretty penny from parking lots. Searching property records, it appears that City Creek Parking—part of City Creek Reserve Inc., a for-profit arm of the LDS Church— is the largest parking operator downtown. It operates 19 lots and garages, with around 13,000 stalls, which represents almost 40 percent of the total parking stalls available downtown.

City Creek Parking also offers the most competitive rates. Not only does the City Creek mall charge only $2 per hour after the two free hours of parking, two of the church-owned parking garages charge only $1 per hour. However, the parking garage west of the Triad Center charges $3 an hour and the garage under the LDS Conference Center charges $10 per day.

Ampco Parking and Diamond Parking are the second and third largest operators respectively, however, in general, neither Ampco nor Diamond Parking own the parking lots/garages they manage. While Ampco operates 10 surface lots and 11 garages, it manages just under 7,500 stalls, or 23 percent of the total stalls downtown.

Diamond Parking operates 8 surface parking lots and 6 garages, but that includes just over 2,200 stalls, or 7 percent of downtown parking stalls.

It tends to be more expensive to park in Ampco and Diamond lots. The majority of Ampco-managed parking garages charge between $2 and $4 an hour, while most garages managed by Diamond charge between $2 and $3 an hour.

Dealing With Dead Space

One of the keys to bringing "dead space" back from the dead is to develop them into residences and businesses that attract more people to downtown. The goal is to make downtown more livable. Malizia says that as more residents choose to live downtown, more amenities (places to eat, drink, shop and celebrate, etc.) will be needed, all of which increases vibrancy. Population density is a key contributor of pedestrian activity. The more people work, live or play on a block, the more pedestrian activity that block will have.

Malizia recommended increasing density and with more multi-family and high-density development, including workforce housing to keep it affordable for middle and lower incomes.

Thus, developing surface parking lots with buildings that attract residents, workers and visitors is a laudable goal. The good news is it could be accomplished without a significant loss of parking. Based on the city's Transportation Division data, if downtown's available surface lots were all utilized for new businesses and residences, and thus removed from the parking inventory, there would still be almost 25,000 parking stalls available to the public. That is a ratio of one parking stall for every 8 residents, still almost double the parking ratio in Denver.

It's already starting to happen in some locations. In 2014, a six-story office building replaced a large surface lot at the intersection of 100 South and 200 East. Just a half a block away, on the 100 South block of 200 East, construction is underway on a seven-story apartment building that replaced a 410-stall surface parking lot.

The site of a former 46-stall parking lot across from Pioneer Park will soon become a six-story apartment building. And Salt Lake City is pushing for development along mid-block streets like Regent and Edison Streets.

But getting the surface lots developed could still be a challenge due to the ownership of the lots. Two religious institutions own large swaths of downtown surface parking: Property Reserve Inc., the private real-estate arm of the LDS Church, and the Greek Orthodox Church of Greater Salt Lake.

The LDS Church owns close to 28 acres of surface parking. The church also owns the only two block-size parking lots, the lot across from the Radisson Hotel on South Temple, and the full city block lot across from the federal courthouse on 400 South. (The late oil and hotel magnate Earl Holding sold the lot to the LDS Church a few years back). The LDS Church did not return calls to City Weekly in response to this story.

The Gateway maintains the second-largest amount of surface parking, the majority of which is tucked away behind buildings.

And the Greek Orthodox Church of Greater Salt Lake, with nearly 3 acres of asphalt from its two surface parking lots on the 200 South block of 300 West, owns the third largest amount of surface parking, all managed by Ampco Parking.

Plan It and They Will Come

According to U of U professor Ewing, "Great downtowns don't have a lot of surface parking." As downtown Salt Lake City grows, the demand for parking will decline as higher-density projects and transit-orientated developments make downtown less car dependent.

Ewing co-authored another study in 2014 with University of Utah Department of City & Metropolitan Planning professor Guang Tian and New York University economics professor William Greene.

The study points out that Salt Lake City's lack of density is essentially the cause of lack of vibrancy. Downtown currently has an estimated population of just over 5,000 residents. But, according to the study, nearly 58,000 more residents would move downtown from nearby metro areas if it were feasible. That's a lot of feet on the street.

The same 2014 study also found that residents valued "complete streets"—streets designed for cars, pedestrians and bicycles—over streets designed just for cars.

Salt Lake City can't force developers to build on the parcels, but it can leverage impact fees and other taxes to incentivize downtown development.

The city itself is close to finalizing the Downtown Community Plan, which, when adopted, would shape land use downtown for the next two decades.

Not only will the plan encourage developing diverse housing options to accommodate new residents, but it also calls for enhancements to downtown's current rail network. City planners want to create a downtown "circulator" by extending TRAX west from Main Street along 400 South to Intermodal Hub at 600 West, helping keep visitors and residents downtown.

A second route would extend TRAX down 400 West off 400 South to reconnect with the current TRAX line at 200 West and 700 South. The 400 South extension would allow for a circular TRAX route and enhance downtown connectivity.

The new plan also proposes a downtown streetcar that would connect 500 East and South Temple to the Intermodal Hub, running east to west on 100 South and 200 South and north to south on both 500 East and West Temple. A second phase would extend the streetcar east to the University of Utah and south to 900 South in the Granary District.

The Downtown Community Plan would modify downtown zoning regulations to help encourage more activity at the street level by making it easier to add ground-floor retail to new and existing buildings. In addition, priority will be to pedestrian-oriented streets and street-level activity instead of parking. Future parking structures will be designed to include active ground-floor uses while surface parking lots will make way for new development.

Surface parking and other downtown dead zones could be phased out in the next two decades if the goals of the current draft of the Downtown Community Plan are realized. But like any plan, according Robinson, its success depends on public buy-in.

In the meantime, the Redevelopment Agency of Salt Lake and the City Council are focusing RDA-managed downtown projects designed to enhance mid-block streets. Construction will soon begin on pedestrian improvements on the 100 South block of Regent Street that will be incorporated into the new Broadway theater. And on Regent and 200 South, construction of the Regent Street Hotel a 20-story mixed-use development, will start next year.

The RDA is looking for a new developer to take over the stalled State Street Plaza project, a 10-story mixed-use project on the 200 South block of State Street. That project includes enlivening Edison Street by building a pedestrian walkway across the street from Gallivan Avenue and will connect State Street with Edison Street.

The key, it seems, to a more vibrant downtown all comes down to Salt Lake City walking its talk: literally getting feet on the street. Robin Hutcheson is the director of Salt Lake City Division of Transportation and Planning who oversees the blueprint of downtown. "As our city grows, having a lively and engaging walk feels much differently than having a desolate and dark walk," she says. "That is where the land use comes in on how we are changing to really support a better walking environment." CW

Isaac Riddle is a Salt Lake City journalist who operates the blog SLCityNews.com.